Bill Harley

2016 INDUCTEE

Children’s Music/Folk Music

THERE’S A LIGHT THAT ALWAYS SHINES

40 Years of Songs & Stories For Everybody with

BILL HARLEY

INTRODUCTION

by Rick Bellaire

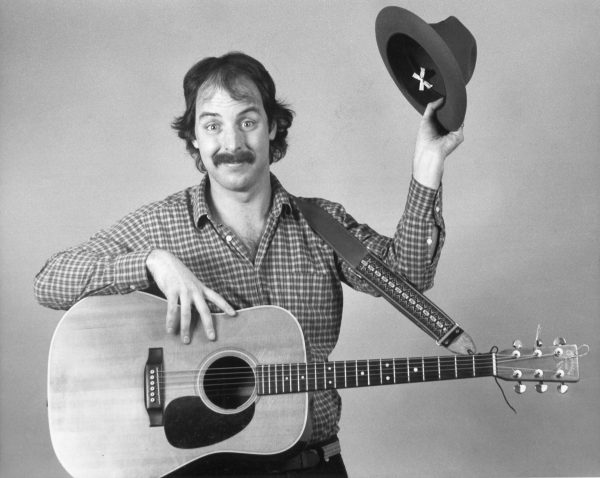

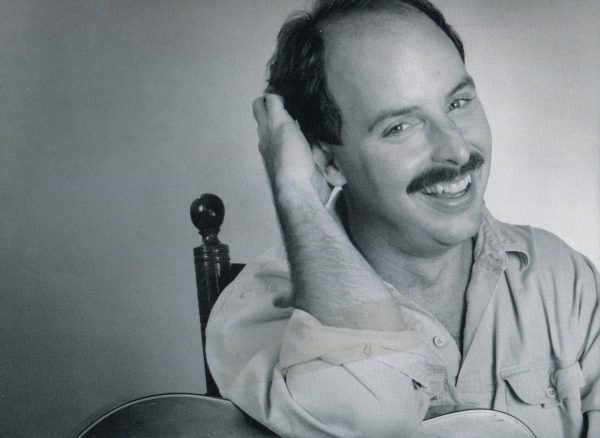

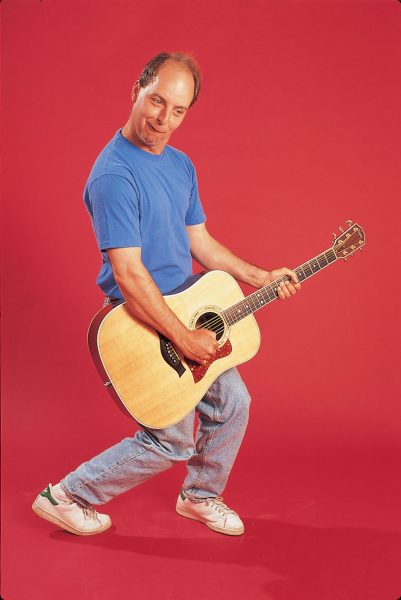

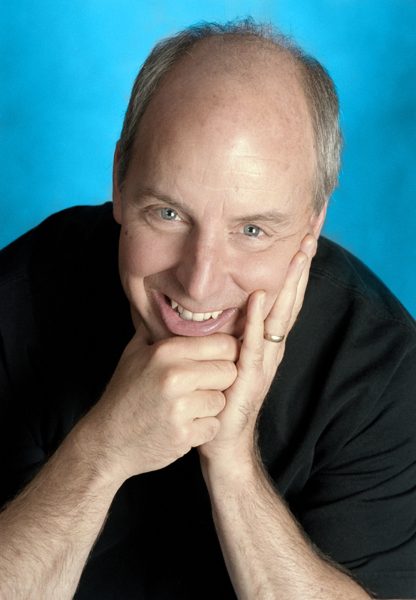

Singer/songwriter/storyteller Bill Harley began performing in 1975. He launched his career as a children’s performer from Providence in 1980 and the following year, he and his wife and manager, Debbie Block, were two of the founders of the Stone Soup Coffeehouse. In 1984, they created Round River Records to release Harley’s first album, Monsters In The Bathroom. His star rose rapidly and over the course of the next four decades, he released more than three dozen best-selling albums. He is one of the most successful musicians in the history of the genre and in 1990, Entertainment Weekly dubbed him “…the Mark Twain of contemporary children’s music.” He is a two-time Grammy award winner taking home trophies for Blah Blah Blah in 2007 and Yes To Running! in 2009. But Harley defies the description of a strictly “children’s music” artist. Along the way, he has lent his voice, in the tradition of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, to social, environmental and political causes and has released five albums of adult folk music. He has had an equally successful career as an author (including his Charlie Bumpers series), storyteller and NPR commentator/host and has won dozens of awards including both Gold and Silver Parents’ Choice awards. In 2010, he was the recipient of the Rhode Island Humanities Council Lifetime Achievement Award and in 2015 received an Honorary Degree from Hamilton College. In April of 2016, Bill Harley was inducted into the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame.

BILL HARLEY IN HIS OWN WORDS

Oral History Interview Conducted and Recorded

by Allen Olsen and Rick Bellaire

March 7, 2021

Zoom meeting done remotely from the homes of Harley in Seekonk, MA, Bellaire in Providence, RI, and Olsen in Charlestown, RI

Allen: My name is Al Olsen. I am here with Bill Harley, 2016 RIMHOF Inductee for Folk & Children’s Music, and the Vice Chair of the Board and Archive Director of RIMHOF Rick Bellaire. I’d like to start at the beginning. This is kind of like This is Your Life – Bill Harley. Can you tell us where you were born, when you were born, and a little about your family and your neighborhood?

Allen: My name is Al Olsen. I am here with Bill Harley, 2016 RIMHOF Inductee for Folk & Children’s Music, and the Vice Chair of the Board and Archive Director of RIMHOF Rick Bellaire. I’d like to start at the beginning. This is kind of like This is Your Life – Bill Harley. Can you tell us where you were born, when you were born, and a little about your family and your neighborhood?

Bill: Sure. I was born in Greenville, Ohio, which is in western Ohio. It’s about fifteen minutes from the Indiana border, and I guess mostly it’s a farm town, it was the county seat of Darke County. My father was a lawyer in the town, and my mom is from Zanesville, Ohio and Columbus, Ohio. My mom was a writer, so I look back on it now and realize that she’s had a pretty big influence on me, in spite of the fact that I would have denied it for most of my life. When I was seven, we moved to Indianapolis, and that’s the place I’ve used to draw on my material for kids. I lived in Indianapolis on the north side from the time I was seven till the time I was sixteen and it was the heart of the Baby Boom generation. In that neighborhood, within two hundred yards of me, there were probably forty children. It was a black hole of children! And then when I was in high school, we moved to the East coast. My dad got a job in New York. We moved to a suburb of New York in Connecticut which was a culture shock. And that’s how I ended up on the East coast. I was a victim of a very normal childhood in many ways. My mom wrote at home, my dad had a job, you know, he went off to work. It was kind of that mid-20th century suburban experience that was very white bread when you look at it now. I have a song that I wrote called “Daddy Played the Phonograph,” which is about my dad. He built a hi-fi stereo with the speakers and the Rek-O-Kut player – that turntable – and he loved big band and Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke and Count Basie and Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday and also classical. Mozart was his guy. He had Bach and Beethoven and Mozart and Handel playing all the time in our house. My mom played some piano. We had a Steinway baby grand in our house that my son has now, that was my mom’s when she was growing up. So, there was music in the house, though neither of my parents were musical per se. My mom played some piano, but it was more an “atmosphere” of music. But I had to go outside of the house to hear popular music. I was not allowed to play The Highwaymen and I was not allowed to play Sam The Sham & The Pharaohs or whatever it was on the stereo. There were no 45s on the stereo – no “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire. That was not allowed on the stereo.

Rick: Wow!

Bill: I think Stereo Review was printing things saying that that kind of music will destroy the needle and the speakers!

Allen: Oh, boy…

Bill: So, I had to go someplace else. I had to go to my friend’s house if I wanted to listen to 45s.

Allen: That’s wild!

Rick: Even The Highwaymen? [Collegiate folk group famous for their version of “Michael, Row The Boat Ashore.”]

Bill: Yeah!

Allen: When were you born, Bill?

Bill: Oh, I’m sorry! I was born in 1954.

Allen: And how did you get to Rhode Island?

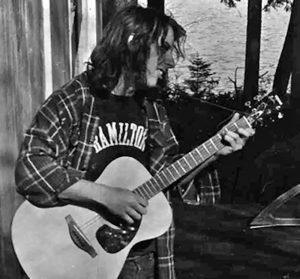

Bill: I went to college, undergrad, in New York state – Hamilton College, in central New York, and freshman year is when I got a guitar. I’d been playing piano. I took those piano lessons everybody had to take at that time, when I was between seven and twelve years old. My perception is that around eleven or twelve years of age is when a lot of people fall off from playing music because they realize that it’s actually hard. Your parents tell you you’re really good, but then you see people who are really good, and you realize you’re not. I think that’s true for most art – there comes a point when you realize being good requires a lot of work. And so I stopped the piano lessons, but I played trumpet through high school. And in high school I started taking piano again; I paid for my own lessons and got a guitar. After college I was living and working in central New York, in Syracuse, and friends of ours encouraged us to come down here to Providence. And my wife, Debbie Block, who’s now my manager, got a job, actually a two year administrative appointment, at Brown [University]. So, we moved down to Providence, and that’s how we ended up here. Been here ever since. Lived in Providence for five years, then bought this old farmhouse that was falling apart out in Seekonk [Massachusetts].

Allen: Right over the…

Bill: [laughter] Crossed the state line. Became contraband. [laughter from all]

Rick: It’s [the farmhouse] not falling apart anymore. It’s beautiful.

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: Very nice place.

Bill: Yeah, I know. Well, we’ve lived here long enough. We’d finally made enough money to fix it up. [laughter]

Allen: Nice! You’ve already answered the next question about the formal music training, with the piano playing. Right?

Bill: Yeah – I did take those piano lessons when I was young. Pretty much torture. One of the funny stories is that we had a piano teacher, Mr. Curtis, and my mom loved him because he came to the house. And I think he might have been getting paid a buck or two [$1.00 per lesson], I don’t know – I mean he was making nothing, and he’d give you a candy bar at the end. But I took [lessons] with him for a couple of years, and I never could read music very well. (I mean,) Reading music is hard. It’s not intuitively obvious what’s going on on the written page. And so, I would listen to him play the piece I was learning and then I would figure out by ear what he was playing. When he came back the next week, I would play it, and he was like, “That’s not quite right,” and then he would show me and I would go, “Okay.” I actually snowed him for over a year. And then finally, one day, he realized I couldn’t read music, and he just left in the middle of the lesson – told my mom he wouldn’t teach me. He left rather than acknowledging my genius. [laughter from all] But then when I was a senior in high school, I decided I wanted to play piano, and what I really wanted to do was play like [famous Rock ’n’ Roll session player] Nicky Hopkins.

Rick & Al: Yes!

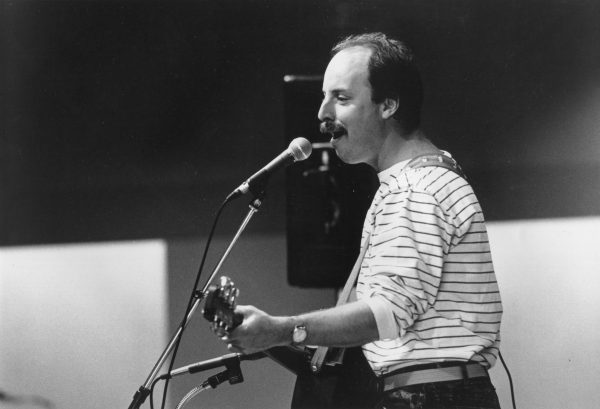

Bill: But, kind of by accident, through a suggestion, I ended up studying with this guy in the town where I lived who was a jazz teacher, and his name was John Mehegan. Mehegan wrote four books on jazz piano and improvisation. He was friends with and wrote liner notes for Les McCann and many others, including Dave Brubeck. And I’d go in, and he could tell right away if I had practiced – he’d listen for five minutes, and if I hadn’t practiced, he’d just get up and leave. And that was the end of the lesson. I have a history of making piano teachers leave. So, then I would practice for the next week. I took lessons from him for about five months. It was boot camp for harmony. Most things that I know musically, like the basis of music theory and practice, I learned in that five months through sheer terror – which may not be a good way to teach! The lesson was eleven o’clock in the morning on Saturdays. He’d come out with a glass, a tumbler, with a brown liquid in it. I didn’t realize until years later – I had already driven him to drink! He was drinking at eleven o’clock in the morning, teaching these kids. But I learned a lot from him, and then the other stuff [I learned] off and on. I took music theory in college and also studied music theory with Taft Khouri. Taft is a teacher around here, a jazz teacher and arranger. [I learned from] mostly the people around me. Musical influences.? So, I came of age at the time of the singer/songwriter thing. So, of course I was listening to Dylan. I was listening to Eric Andersen – you know that kind of Greenwich Village [scene] and Tom Paxton who I ended up becoming friends with. Tom was very encouraging to me early on. Steve Goodman was a huge influence. Jackson Browne’s early albums were very influential to me. At that point I was learning by copying what they were doing. I’d write a Dylan song, or a Neil Young Song, or a John Prine song or a Tom Paxton song. And folk music, it’s like what they say about country [music): it’s three chords and the truth. I think every musician at that point in time– [we] don’t have to do this anymore – but when you were trying to learn a song, you would just listen to the recording over and over and over again and try to figure out the chord.You had to find the chord yourself, you know, and figure out what it was and sometimes weird things happened…I remember a friend of mine was playing in a rock band, and he was trying to figure out how to play all the Rolling Stones’ tunes, and he didn’t know that [Keith] Richards was playing in open G tuning. He was trying to do all those sounds with a barre chord, playing a G chord with a barre over the top, you know? [laughter and agreement] And I think all of us were in that position of having to practice ear [training]. We had to develop our ears in order to understand. And fingerpicking, like how did they do that? You know, drop D tuning. When I found out about drop D tuning, it was like a religious experience. “Oh my God! Look at this!”

Rick: If I could backtrack just a tad.

Bill: Sure!

Rick: You earlier mentioned the Highwaymen. The “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” guys.

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: They were local [Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut]. One of them was a Rhode Islander [Bob Burnett].

Bill: That’s right, and I met him at some point. I was given an award from the Chorus of East Providence, and he was getting one, too, shortly before he died. But all that kind of folk stuff, I missed the first time around… [laughter].

Rick: When you were little, a kid, it would have been the Peter, Paul & Mary and The Brothers Four kind of thing, leading up to Dylan and Joan [Baez].

Bill: Yeah. My older cousins were listening to Peter, Paul & Mary, [you know] it was 1961- I would have been seven. I have to say I didn’t really have access to folk and acoustic music until I went to college. And so, when I could, I was listening to top forty radio. In Indianapolis the pop station was WIFE. But I found other stations, too. I have a long story I tell, as a performer, about listening to my brother’s radio, discovering CKLW. It was the station in Windsor, Ontario, but it was the “Voice of Motown,” and that’s the first place I heard The Four Tops and Mitch Ryder and Smokey Robinson and all that stuff. I would listen to it because my dad wasn’t listening to, right? It was a generational thing. And it would drive my dad [crazy]. Finally, I remember, when I got a Blood, Sweat & Tears album, he said something like,“Oh, thank God, something I can listen to!” The next album I got was a Creedence Clearwater [Revival] album “Bayou Country”, and it had “Graveyard Train” on it and the guy plays the same bass line for nine minutes! [laughter and mouths bass line]. Like fingernails on a chalkboard for my dad. Well, anyway… [laughter]

Allen: Moving back, you mentioned that you played trombone in an ensemble, Bill? Did you say that?

Bill: Trumpet. Trumpet.

Allen: Can you tell us about that early music involvement in performance?

Bill: I started playing trumpet when I was in fifth grade. And then in seventh grade I played in the junior high school band. In Indiana, school band is really important. Band is a big deal – and so I was in band seventh through ninth grades in Indiana. And the conductor was really serious and really good. He was also a brass player. So, I didn’t practice as much as I should [have]. I should say my older brother is a musician. He plays French horn. And I kind of watched what he went through trying to be a professional musician in the classical world, which is really brutal. He’s good, but what it takes to be in the classical world is not [easy], it was really hard to watch. Especially for my parents, knowing he probably wasn’t gonna be good enough to do get a seat in an important orchestra. But anyway, when I was in eighth and ninth grade, the father of the first chair trumpet player in the band, put together a small ensemble, like a Herb Alpert group. [laughter from Al and Rick] I was the second trumpet player, and there was an electric bass player, and a drummer, and probably a trombone player. There might have been an electric guitar. I can’t remember. And we did “[A] Taste of Honey” and “What Now My Love?” and…

Rick: “The Lonely Bull” [by Herb Alpert’s band The Tijuana Brass]?

Bill: Yes! “The Lonely Bull!” The first trumpet player, John, was really good.He had a Bach trumpet, and I had a dinged up Selmer. I remember the first time that we were on stage for a performance. We had been practicing in some basement, and we played at the talent show. I don’t think I’d ever heard an electric bass and a drum play at the same time, and it was behind me. And the overhead strip lights were on, red and blue and white, and I thought “Oh, my God. This is amazing!” As a solo performer now, I don’t get this a lot, but band players know that there’s an aura of sound around you when you’re playing with a group that’s really indescribable, that the listeners have only an inkling about. That was the first time that I felt that. As a solo performer, all your energy is going out to the audience. And as a guitar player, I have to be able to play so that I don’t think about it so that I can pay attention to the audience. When you’re playing in an ensemble, the music’s carrying you, and you’re just part of it. Pretty amazing.

Allen: Beautiful. And was your first performance on a more professional level when you got to Hamilton College, or did something happen before then when you were in a band?

Bill: Yeah. When at Hamilton, I was in a really bad rock band, and I played keyboards, and it was a borrowed keyboard. It was an organ, and I didn’t know anything about electric instruments at all. It was one of those organs where the speaker was in front of you, and you had a volume thing [lever] with your knee. You’d shift your knee to increase it [volume], and I could never hear myself ‘cause the music was all out front. I didn’t know what I was playing. I remember we were playing “Wayward Son” [“Carry On, Wayward Son,” Kansas] and Steely Dan. I would figure out the chords, and they would all say “You’re playing too loud, man!” I never knew what I was playing because all the sound was in front of me! So, I did that, and then I started to write songs and began to play at local coffeehouses. There was a folk festival at the college there every year, and I was a freshman, and I’d written a couple of songs. There was a competition – I didn’t [do well], I wasn’t a finalist. But this guy came up to me, a judge, and he said “I don’t like songwriters,” – he was a traditional musician – “but I like you. You have something to say. I don’t like songwriters, but you’re okay.” And this was Jeff Warner! His father collected “Tom Dooley” in North Carolina [in its original form, “Tom Dula”], and he’s still around [performing as Jeff Warner & Jeff Davis]. He’s a traditional musician; he’s very well considered. And so, he tapped me on the shoulder. And that was the first [inkling I was on the right track]. I mean, I was a freshman in college, and I knew six chords.

Allen: So, what happened at [Hamilton] college? Did something turn a light on for you to point you in a direction?

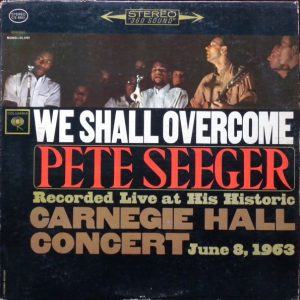

Bill: You know, this is…[laughter]; I always think of David Crosby who’s no role model for anybody. There’re two reasons that a guy gets a guitar. One of them is to play music. [laughter from Allen and Rick] So, you know, I was not immune to that. But it was also a time of ferment. It was the rear-end of the Vietnam War. I was very active politically. I knew of Pete Seeger, but at that point I heard one of the most seminal albums for me in terms of folk music – the 1963 We Shall Overcome concert [at Carnegie Hall]. It was just an amazing album where he shows that music has a cultural function which has been really important to me – where it’s not just someone talking about themselves. And Pete said this to me, “The main purpose of music is to build community.” That’s what its main function is, in the history of humankind. So, I began to pay attention to that. The other thing was my friends and I, one of them who’s now my wife Debbie, started a day camp in the summer. I had a guitar and was very comfortable with kids. First thing in the morning, I would sing two or three songs – at the end of the day, we would sing songs, and I would tell some stories. That was where I cut my teeth on how to work with kids, and also find out what worked with them and what didn’t.

Allen: And that was when you were at college?

Bill: That was during college.

Rick: Debbie [Block] was with you at college.

Bill: Yeah, we met in college. And the other couple we did this with was Greg Marsello, whose family ran Imperial Pearl on Manton Avenue in Providence and when it was going down, he came back and managed that transition. He went on to work in continuing education his whole life and his wife, Melinda Foley ended up being the head of the lower school at Friends Academy out in Dartmouth [Massachusetts]. What happened to us then [at Hamilton College] informed who we became.

Ed. Shorty after their arrival in Providence, the two couples formed the Providence Learning Connection (later shortened to just Learning Connection) on the East Side. It was a community learning center which offered courses on a wide and esoteric range of subjects, anything from guitar lessons to French cooking to fly fishing, meditation and knitting. The center operated for more than thirty years before closing down in 2014.

Rick: I want to make sure I’ve got this straight. The pivotal thing was you were basically doing a singer/songwriter thing, a coffeehouse thing, in college, but it was still during college that [you] began working with the children and realized “Hey…”

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: “…I might have something here.”

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: Okay. Did you have any idea, [was it] junior or senior [year] or something like that?

Bill: I think we might’ve started the camp maybe sophomore year. And that was a great deal for the people in town. I think we charged fifteen bucks a week for a kid to camp at our camp for six hours a day or something like that. We were idiots. [laughter from all] Like, “Oh, my God,” babysitting for fifteen dollars a week!” Yeah, so, it was either sophomore or junior year. That was what I did. And once again, to go back to Pete [Seeger], Pete recorded a bunch of kids’ albums. And when you went to a concert, you were probably going to get a couple of kids’ songs. That was part of the deal. He’d sing “Skip To My Lou,” and talk about the background of the song or something, ‘cause that’s the way Pete was. And so that just made sense to me. You know, to make a living, you have to be put in a box, so people know how to market you, but I’ve never been very comfortable with being identified one way or another. It’s just one of the things about the music industry, and it doesn’t make sense to me, but it’s alright.

Rick: Similar to Pete though [Seeger] and Woody [Guthrie].

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: It’s a family thing as opposed to just doing it all on your own.

Bill: Yeah. I remember when I was in college I went to see Pete perform – I was in New York with Debbie’s family – but I guess I got a ticket for myself. He [Seeger] would do a concert every Thanksgiving at Carnegie Hall. And towards the end Arlo [Guthrie] came with him a lot. And I remember [laughter] I was standing outside, I think I was waiting for somebody to come, and there’s this guy next to me whose standing with a ticket waiting for somebody to come, and I looked over, [I] was like “Are you Alan Ginsberg?” He said, “Yeah.” I said “Okay!” [laughter] Anyway, that night Pete said, “I got three generations of my family here tonight, and I hope that you do, too.” And I remember sitting there thinking, “Right! That’s what I want. I want to do something that three generations can come to and be entertained and be moved. That’s what I want.” And it’s really hard in this culture to make that case. Like say you’re doing kids’ music, people think you’re gonna do “Itsy Bitsy Spider” for forty-five minutes. My image is – I want the kids sitting on the stairs – halfway down, listening to the songs and the stories that the adults are telling, and learning from that. In many ways, Pete was the biggest influence on my perception of what my job is. I can’t remember when I first met him. There was an organization called “Songs of Freedom and Struggle,” which then became “People’s Music Network,” it did political music. They’re still around. And I would go to those conferences. And Pete was there, sleeping on a mat on a gym floor with everyone else, and I would introduce myself to him, but so would everybody else. At one of them, I sang an anti-nuke song I had written – it was the middle of the anti-nuke movement – and Pete came up to me right afterwards and he said, “That’s a great song. I wanna sing it.” He sat down and wrote out the music to it right there. [Said] “So, I’m gonna sing this tomorrow night.” And I was like, “Huh?!” [laughter] You know? And so that might have been it; you know, that might’ve been when I first began to know him. But actually, no! When I was just out of college, I remember writing him a letter, saying what I was trying to tell stories and sing songs, when I was in Syracuse [New York] before I did it as a job and said, “I want some advice.” And he wrote back. He wrote this letter and said read this book and do this and do this and do that. Debbie got to know him too; she was on the board of the Sing Out! foundation, the magazine – and we got to know Toshi [Seeger, wife of Pete and filmmaker], and we know Mika [daughter of Pete and Toshi and a ceramic artist] who lives in Tiverton. But I’m not special, in the sense that Pete did that for thousands of people, but it was pretty amazing to have the phone ring and it would be Pete because he had a question. [laughter] I have to go out the door because I’m late getting somewhere, and Pete Seeger’s on the phone? What am I supposed to do? I’m late for something. So…

Rick: …you took the call. [laughter]

Bill: Yeah. Yeah. You take the call.

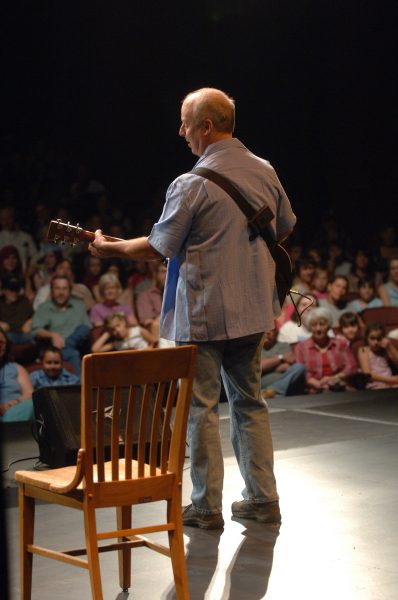

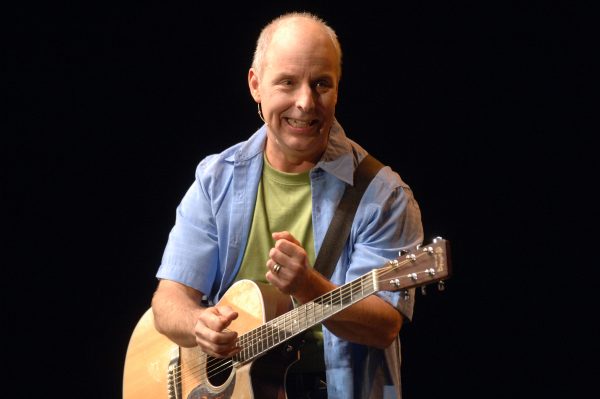

If you’ll gather ’round me children, a story I will tell* – Bill Harley doing what he does best (*Woody Guthrie from his song “Pretty Boy Floyd”)

Allen: Well, Rick, do you wanna go with the artist questions?

Rick: Well, I sound like a broken record. Bill has been preemptively answering some of my questions. [laughter]

Bill: I know. I’m sorry! That’s the way…I’m a storyteller!

Rick: That is great! [laughter from Rick and Allen] My point is I was going to say besides Pete, I hear Woody, but as far as your children’s or family-oriented stuff goes, it seems very original. It doesn’t seem [like] the other children’s stuff you hear.

Bill: I think a good song’s a good song, and a good song ought to work on a couple of different levels. A lot of children’s material – whether it’s songs or movies or anything – is prescriptive : “Here’s who you should be,” and I’ve always kind of bucked against that. I mean, I have a song about wearing your helmet, and a song about washing your hands – you know, public health things. But I’m much more interested in being descriptive. I think a good song says, “Do you feel this?” “Does this happen to you?” And so, you know the job of a storyteller – which is why my songs tend to be more narrative – my job is to name things. Not prescribe behavior, but describe behavior or events and say, “Does this happen to you?” ‘Cause when you do that, you’re assuming the intelligence of the audience, putting yourself on the same level as the audience. And a lot of times in performances, especially for children, someone may be saying, “This is something you need to know,” as opposed to “This is something that I want to share.” Those are two very different postures, and in kids’ entertainment tends either be stupid and honor anarchy totally, or it’s preachy. What I’m trying to do is talk about the emotional lives of kids, about who they are at this point rather than who they should become. And it feels like if you do that, you’re honoring their lives, and that you’re affirming what their experiences are. That’s been the basis of a lot of my writing, and I think that that’s true for good songwriting. I’ve always asked myself, “What’s the universal in this song or story? What am I saying that identifies something in the human condition?” And if can you do that, then you’re gonna make that connection with the audience. Whatever success I’ve had, one of the reasons is because of that – because I think that kids and parents trust me on that level. Some parents get uncomfortable with how direct I am with some issues. Although I’m not beating them over the head, but that’s one reason that I’ve managed to do this for a living.

Rick: You touched on this as well, and it relates to what you’re speaking about now. A lot of your audience are children of people our age [Bill and Rick], and now you’re seeing those people who are now in their twenties and thirties buying your music and attending your concerts with their children. So, you’ve got grandparents…

Rick: You touched on this as well, and it relates to what you’re speaking about now. A lot of your audience are children of people our age [Bill and Rick], and now you’re seeing those people who are now in their twenties and thirties buying your music and attending your concerts with their children. So, you’ve got grandparents…

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: … and kids. And that must be [part of] what you envisioned or what you might have just hoped for.

Bill: Yeah it is, and I have to remind myself [of] that ‘cause I’m just like everybody else: I’m trying to keep my head above water. But there’s a certain part of me – you stand back, you look, you see, a grandmother brings their child, their granddaughter or grandson to your show, and she says, “This is the second kid I’ve brought to your show.” And I remember the concert with Pete [Seeger] and think, “Wow! That’s a long time to be doing it.” One other aspect of music for kids that’s interesting is you’re allowed to explore musical styles in a way a lot of musicians aren’t [able to]. I think my albums [show that]. When I was really producing a lot of albums, I was exploring different music styles. When I wanted to do a doo-wop song- I would listen to a lot of doo-wop. I was listening to a lot of Gospel – The Swan Silvertones – and I would write a Gospel tune for kids. I don’t mean religious, but in the Gospel style, and then I would listen to say, Toots & The Maytals [laughter] and we’d try to figure out how to make that sound. And then I would be listening to Appalachian ballads with banjo, you know frailing [style] banjo, and because it was kid’s music, nobody was gonna call me out on like, “Who do you think you are”? I was allowed to do that. And so that’s certain kind of approach that’s worked out well with children’s music – my openness to different musical styles. I think I just got off of the topic of what we were just talking about…

Rick: Oh, no, no. [laughter]

Bill: I’m pretty omnivorous in my musical tastes. But that cross-fertilization is more and more common.When I run into really great folk musicians now, a lot of them have some kind of classical training. And a lot of classical musicians are really interested in traditional material, or they’re interested in what some other musicians are doing, you know, a string quartet is playing some arrangement of a Talking Heads’ song or something like that. I think those worlds have kind of broken down and I like that. This somehow relates to me being the host for the Rhode Island Philharmonic Family Concerts for several years!

Rick: Oh!

Bill: And that was a blast. ‘Cause I had grown up listening to the stuff, and now was trying to find a way to explain it in a very prosaic way to kids and their parents, who probably knew not much more than their children, when they came into that concert hall. In the middle of the classical concert, I might sing a song on guitar.

Rick: Edger Meyer, Yo-Yo Ma, and Chris Thile – they have that trio.

Bill: Yes. Exactly!

Rick: I think that’s fabulous.

Bill: Yeah. Yeah, and Chris Thile and all those guys are monsters.

Rick: They’re putting the band [Nickel Creek] back together for a couple of live streaming broadcasts.

Rick: Al, don’t let me monopolize the questioning.

Allen: Oh, no. I thought we were up to artists; the questions that you wanted to ask him. For example, you were going to say that it’s not all about children’s music, that there’s a lot of folk music stuff [there], too.

Bill: Yeah, so we should probably talk about when I moved here [to the Providence area], I was seeing myself as a folkie although you know we were all tainted. There’s not much purity in the music world. We’re all mongrels. But, I found the people who were playing folk music and at the time it was Steve Snyder, Kate Katzberg and Joyce Katzberg. There was a Black musician around here, Bill Brown, who played some acoustic blues. Then there was the whole thing that was happening down in Newport. I got here at the tail end of that ‘cause Salt [legendary folk venue in Newport] had just closed and the folk festival had been shut down. When the Navy pulled out, things went downhill there for a while. And Paul Geremia. Paul was around.

Rick: Pat Sky, Cheryl Wheeler.

Bill: Cheryl and Pat Sky. So, there were about five or six of us who started Stone Soup. Actually, we went to a conference that Pete [Seeger] spoke at. I went with Steve Snyder. And Pete said, “There ought to be coffeehouses everywhere! Go home and start a coffeehouse!” That’s the way he spoke [mimicking Seeger], “You know, you all have to…” and so on the way home Steve and I said “Well, let’s start a coffee house.” We put together a group of people. Stone Soup had a very political bent. Steve is a really, really talented man, and now he’s a producer for The World at WGBH (NPR Boston) and he produced my first couple [of] albums, he’s much better musically than me – but anyway, we started doing shows at Stone Soup Coffee House (on Hope Street on the East Side of Providence]. We’d first started meeting in peoples’ living rooms. And at that point, I was one of the first staff people at the Providence Learning Connection. [That’s] another thing that I was doing at the time. And so, we met at the Learning Connection office, above the Podrat Coin Exchange at 769 Hope Street. Sixty people crammed up there. It was completely illegal. I remember we had [Paul] Geremia – he played up there, Bill Staines played up there, I know Charlie King played up there. The coffeehouse moved around. For ten or fifteen years, that was my musical home. I ran the open mic; there was always a Hoot when there was a performer, and I ran the Hoot.

I was writing a song a week, and I would get up there every week and I would try out the song. Also, TryWorks was a great coffee house in New Bedford [Massachusetts], that was run by Maggi Peirce who’s from Belfast. It was at a Unitarian meeting house. It had this beautiful sound [acoustics]. Everybody sang there. The audience knew a bunch of traditional songs and would join in. It was amazing.

Rick: These would be songs that wound up on Coyote [Harley’s first adult folk album) or…

Bill: Yup.

Rick: …the straighter folk…

Bill: Yes. Although I would have also [sung] “Monsters in the Bathroom” there if I had just written it.

Rick: [laughter]

Bill: I didn’t care. Monsters in the Bathroom – that was my first album for children. Recording that was seriously “fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” We recorded half of that live at an elementary school in Warwick, all one take and we got away with it. I knew the material well enough, but I look back on it now – I would never do that now, assume that I can get a recording out of one live performance.

Rick: It worked. [laughter]

Bill: Yeah. Work in our area is still really important to me. Being a local artist really matters to me. I live in Massachusetts now, but Providence is really my artistic home. And I’ve been lucky enough to work with great artists around here. Two of my most enduring partnerships have been with David Correia, who has recorded and mixed most of my recordings at Celebration Sounds, and Keith Munslow, who has been my musical co-conspirator for a lot of performances and recordings. I feel lucky to have such talented people working with me over the years.

Rick: While we’re on that subject, just to save time at the end, most of your stuff is now available to download. You’re not offering CDs anymore?

Bill: Yeah, we have CDs for most things. And I’ve got this brand new recording. It’s just coming out now actually. But we do have CDs available; they’re in our [basement]. We just did our taxes, and we’re trying to decide, “Should we write ‘em off this year?” [laughter] Thousands of CDs that are gonna stay there until my children have to empty the basement after we’re gone. [laughter from all] When do we write ‘em off? Most of the stuff is on CD; Coyote we don’t have on CD.

Rick: Right. But it is digitized.

Bill: It is digitized.

Rick: So, is the plan to get them all in a downloadable form to keep them in the catalog?

Bill: I think they are.

Rick: There’s only, I’d say, about half of them [digitized].

Bill: Oh, is that right?

Rick: Unless I’m looking at the site wrong, it seems like only a third or a half, maybe.

Bill: Well, yes. But then we are gonna get it all, it would all be, for as long as this particular format [download] lasts. [laughter]

Rick: Well, they can’t do away with air. [laughter from all] You know, downloading can’t die, you know like when they got rid of the CDs. I’d love to see your stuff still be available in CD, you know?

Bill: Yeah – you know, this is a longer and deeper question, but at this point there is a question about what the value of a recording is; there’s no assigned value for a recording. I did a show two weeks ago, a streamed show, and my sons Noah and Dylan played on it, and it was kind of an album release. And we just said, “If you buy a ticket to the show, you get a recording.”

Rick: Shows seem to be the thing for everyone all the way up to The Rolling Stones, and even songwriting royalties are obviously not what they should be, but the recordings still perpetuate your body of work and keep up interest in you as an artist, you know, for [booking] performances if nothing else.

Bill: Yeah, and you know I’m at a point in my life where I want to do good work, but everything is kind of gravy – I’m not worried about the money aspect of it. I was talking about this with my sons last night, who are both musicians. My oldest son Noah is finishing up a recording, and he said, “I’m asking myself, ’What do I want out of this? Do I want to sell ten thousand units? Do I want to be invited to the Newport Folk Festival? What is the goal of it?’” [For me] it’s not like I’m a hot property. At this point, it would be really great if somebody else took these songs and sang ‘em other than me. It’s like that. You just do the work and hope it gets listened to.

Rick: It will.

Allen: Absolutely!

Bill: Thanks.

Ed. Bill’s work has indeed been well-curated: as of this writing (March, 2021), his entire recorded output has been documented and digitally preserved and is available for downloading from his own label, Round River Records, through his website; many of the titles still remain available on CD and DVD.

Allen: Um, do we want to ask about the opera?

Rick: I was saving that for last since it seems to be the newest thing if that’s alright. I have a couple of other questions if it’s okay with Bill. You were briefly with A&M Records which is one of the major labels of our time.

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: I think it only lasted for one album.

Ed. Bill was with A&M Records for two releases: Who Made This Mess? (1992) and Big Big World (1993).

Bill: A&M was early-in on the kids’ music and kind of struck gold with Raffi. Raffi was in the right place at the right time for the Baby Boom generation. Raffi’s genius for those early albums was his simplicity. It’s just, “Here’s the song that you might want to know,” and he was very sincere. And A&M made a boatload of money from Raffi, and so they kind of cooked up this children’s division that had a bunch of people on it. I’m trying to remember who else was on that label at that time…Sharon, Lois & Bram [14 albums distributed by A&M Children’s Records] and a bunch of Canadian artists [including Susan Hammond’s Classical Kids and Fred Penner], Tom Chapin and Shari Lewis. Canadian artists were ahead of us in terms of kids’ music from that [period], but we were all making our own recordings, too. There was a guy in California I worked with, Peter Alsop, who made great kids’ recordings and became a great friend. Peter does not have an editor. [laughter] Peter was constantly getting in trouble for things he would say on stage and for the challenging songs he wrote. He was like the bad boy – he and Barry Polisar.

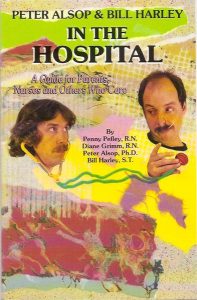

Ed. In the summer of l988, Diane Grimm and Penny Pefley, two Registered Nurses at Children’s Hospital in Seattle, Washington, began discussing the power and possibilities of using music and humor to make a difference in the lives of children who are in the hospital. As the idea grew and took shape, the vision of a recording for these special children emerged. They contacted Peter Alsop, a popular children’s music artist with a Ph.D. in Educational Psychology, and convinced him of the value of such an undertaking and he in turn contacted singer-songwriter-storyteller Bill Harley and asked him if he would like to collaborate on the project. Penny and Diane were consulted frequently as “nurse advisors” and editors while Peter and Bill wrote the stories, songs and dialogue. The project was released as a cassette/book combo in 1989 on Alsop’s Moose School Records label and has proven to be a perennial favorite. It was reissued in 2006 with the recording on CD and is also available for downloading or streaming from all the major services.

A picture paints a thousand words! Peter Alsop & Bill Harley wreaking havoc in the hallways on the cover of the 2006 CD reissue of “In The Hospital.”

Barry Polisar was seriously the bad boy of children’s music. I mean, Barry had, like, functional guitar, functional voice, and would write great songs like, “Shut Up in the Library” [laughter from all] which was total anarchy. It was great! Really great. A friend of mine, Regina Kelland, who had been Peter Alsop’s manager, really liked my work, became the head of A&M and she immediately wanted to sign me. In the long run, A&M may have realized that for kid’s music they couldn’t manage human artists. They could manage franchise characters better. There was more money to be made from [Teenage] Mutant Ninja Turtles than there was in somebody who actually was thinking about what they were doing. But we were there for awhile and A&M wanted to sign me.So, through family connections, my lawyer was a guy named David Braun who was a close friend of Deb’s [Block] family. Deb’s father was involved with Viacom and had friends in the entertainment industry. So, David had known me forever, and he had been the head of Polydor [Records] for a while, he was [Bob] Dylan’s lawyer for a while, was Neil Diamond’s lawyer, and so he said, “I’m going to handle this for you, Bill.” [laughter] We would go out for lunch. He said, “Bill, if you’re gonna be big, you gotta lose the guitar, Bill. They want all of you. Neil [Diamond] gave up the guitar. He doesn’t perform on the guitar. They want all of you, Bill.” And I was like “OK, David.” So Dave went in and negotiated the contract, and my friend Reggie, the head of the division, she called up, she said [nonchalantly], “It was intense. I’ll just say that David threw chairs.” [laughter from all] I don’t think that was the way that I would have operated. It was just a total L.A. thing that happened. But they gave me $30,000.00 to make an album, which was at the time I think when Axel Rose [and Guns n’ Roses] had already spent twenty-seven billion on three cuts or something. But it was all the money in the world to me. So we did horn arrangements and then we made a video. I was, briefly, maybe a hot property and was courted by three four different television production companies about doing a kids’ TV show, and I managed to ruin every one of them! [laughter from Rick and Al] There was one – I was gonna get hired to do a five-day-a-week show for Nickelodeon.

Rick: Wow!

Bill: And they were talking about us moving to Orlando, my whole family moving down there, and I went down for the final interview/audition. And the guy said, “If you don’t blow it, this gig is yours.” And I went in, and I blew it! I didn’t practice the song that they gave me to practice; I mean, it’s embarrassing. [laughter] And I walked out of there thinking [bangs fist on desk], “What was that?” I took the train down to New York in the morning, I went in and I bombed, and I rode back, and I thought, “I guess didn’t wanna do that.” And the next week, I went to Paul Cuffee School [Providence] and said, “I want to be your artist in residence,” you know, a school for inner city kids. So, that was only one of the ones that I blew. So, evidently, I didn’t want to do it.

Rick: We [RIMHOF Archives] proudly have – I think I got it when I was working at a record store on Thayer Street [Providence] – your Anthem Artists promo package with the A&M logo on your photo…

Allen: Wow.

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: …so, you were a major label artist! [laughter]

Bill: You know, it’s something you can use as a calling card. And actually, what I should say about A&M [is that] when it didn’t work out, for a minimal amount of money, they gave me back all the masters and all the rights to the video. And they could’ve, I mean – you know the stories about major labels screwing artists – and I have to say they did not do that at all. So, I’m grateful for to them for that ‘cause I thought we’d never get back Big Big World but we did!

Ed. Big Big World was Harley’s second album for A&M.

Rick: Alright. What else do you have there, Al? I kind of wanted to save Weedpatch (the opera) ’til the end since that is the latest thing; and you have this new album coming [too].

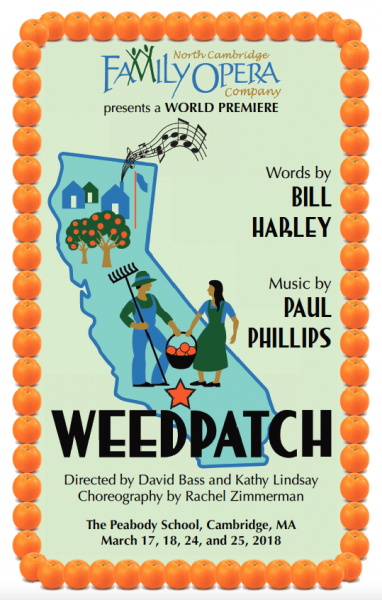

Ed. Weedpatch is an opera composed by Bill Harley (words) and Paul Phillips (music) which had its debut performance in March, 2018.

Bill: I was approached by this little, funky opera company, the North Cambridge Family Opera Company, which has an incredible history in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They wanted me to write a musical and I already had an idea. Previously, I was developing a musical for families for Oskar Eustis when he was [artistic director] at Trinity Rep. I’d met him at a playwrights’ lab at Sundance [Institute]. He was there working with [playwright-author-screenwriter] Tony Kushner on Angels in America and I was working on this solo theater piece which never went anywhere. But we got to be friends and so, when he came to Providence, I did some work for him, and I said I want to write a musical. I’d read a book somebody had given me about the federal migrant labor camp which is one of the settings in The Grapes of Wrath. It’s in Arvin [California] and the book was about how the kids were discriminated against in the Kern County [California] schools. And so, the superintendent of schools said, “Let’s build your own school.” And so the kids and their parents built this school, and it was just this beautiful thing that happened for two or three years there at the end of the ‘30s – 1939, 1940. It was a beautiful bloom, and I remember when I read this book I said, “This is [perfect for] a musical because we’ve got all [the background material].” The WPA went in and recorded all the traditional songs and stuff like that, so it’s naturally based. So, I was carrying that around. Then, I approached Paul Phillips, a composer who was the Director of Orchestras at Brown University. We had worked together on some other stuff, arranging some of my stuff for orchestra. We worked on it. It took longer than it should have. And it’s really beautiful and I’m hoping it has legs. I was librettist, by and large, but I didn’t really get to finish my work. So, I’m hoping if it’s going to be performed again, I get to go back and clean up some of the stuff. It was a challenging art exercise, and there’s some really good stuff in it. And I don’t know; it might have a life. I think the opera company may produce it again and [other] people have expressed interest.

Rick: I guess you were on your own [when] writing. Were there actual constraints from opera composing or even from Broadway composing, or did you just write?

Bill: Well, it was an interesting experience. When I started to do it, I went to school myself on it. [Stephen] Sondheim has great books. He has two great books of the lyrics of his musicals, and he talks about writing the lyrics for those, and I learned a lot from that. I read a lot of stuff about musical theater. And this one was particularly challenging because they did not want any dialogue – there was no spoken word in it, so we had to communicate the story all through singing. But we broke the story down and figured out where the arias were, where the trios were, and all that other stuff and how it was all gonna work. And then I went off and wrote the lyrics and gave them to Paul [Phillips]. There was not as much interplay as I would have appreciated. It was interesting because, obviously, I think if you want something to be really good, you have to let go of things. Your vision is probably not big enough. I mean, this happens in the recording studio all the time. You know, somebody comes in and you thought you knew what you wanted, but the guitar player says, “I was thinking of this.” And if you’re not open, you might not see that it’s a better idea. Or the engineer says, “I don’t think this belongs here.” That’s why you have a producer, although I produce most of my own stuff. But you want someone else. I’ve seen it many times…artists who are really talented, but they can’t let go of their particular vision to make it bigger. And I think that’s the tension you’re always feeling. If you think about the artists who have kicked it up to a [high] level, one of their abilities is to surround themselves with people who are gonna make the project bigger. I remember reading an interview with Mark Knopfler. He said, “My job when I’m making a recording is to be the worst musician in the room.” Mark Knopfler [former leader of Dire Straits], he has a challenge doing that. I don’t have that challenge. [laughter all around] I’m a pretty good conceptual artist, but there’s a better guitar player than me, and there’s a better singer than me, like right around the corner, you know?

Rick: But sometimes it’s your guitar that goes with those songs.

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: You know what I mean?

Bill: Yeah.

Rick: It’s not just for you alone. You’re almost punctuating your…

Bill: Yeah. And you learn that. You know, you do learn that. And that’s a whole other…

Rick: You’re a guitar player!

Bill: Thank you very much. I appreciate that. You know – and I might have said this to you – one of things about music is that I think most musicians, except for maybe like Yo-Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, feel illegitimate in the sense that you know, if you’re a real musician, you know how big the world of music is. And if you’re really good you might’ve had a good part of it, but most of us have this very little part. So, what we’re really aware of is all this other stuff that we can’t do. I think it’s a very humbling thing.

Rick: And I have one more, but Al, do you wanna ask Bill some stuff here?

Allen: Well, I thought that on that subject, the humbling, why not ask about the Grammys? [laughter from Bill and Rick]

Bill: So, you know…who knew? [laughter] I think I was nominated four times and didn’t win. I think I won on the fifth time or something like that; maybe nominated three times and I won on the fourth time.

Ed. Bill Harley was nominated for seven Grammys and won two.

I’ve been nominated for both the Spoken Word for Children, which is a category that’s now gone, and Recordings for Children/Music for Children. They’ve combined both of those things. And I think that there’s a loss there, but there’s a hundred and six categories. The first time I went, I just couldn’t believe it. It was a total shock. I would hear from people I knew in the industry like musicians, who’d say about my recording, “God, I love this!” Then I’d reply, “Really?” I remember the first time I was at the Grammys, there was a guy there – I can’t remember which genre it was – but it was a guy from Firesign Theatre. He was nominated. I thought, “Oh, my God!” – I gotta introduce myself. He said, “Who are you?” I said, “Bill Harley.” He said, “Bill Harley! Oh man, my kids love your album!”

Allen: Wow!

Ed. In 1998, the comedy troupe Firesign Theatre’s Give Me Immortality or Give Me Death was nominated for Best Spoken Comedy Album. That was Bill’s first year at the Grammys; he was nominated for Best Spoken Word Album For Children for Weezie and The Moonpies. As this was a group nomination for the Firesigns, Bill might have encountered any one of the members: Peter Bergman, Philip Proctor, Phil Austin or David Ossman.

Bill: I was like – undone! You know, you can kill me now – Firesign Theatre is listening to my recordings! So there’s that. I just I couldn’t believe it the first couple of times. And then after a while…at that point, you know Children’s Television Workshop and Disney were winning for the recordings of read-aloud books and stuff like that. Through my nominations, I got to know two guys who wrote songs for Disney. They’d written thousands of songs. And they’re both really good, and they were saying, “God, we hate it when you’re nominated because we’re afraid you’re gonna beat us.”

Rick: Yeah!

Bill: [laughter] And I said, “You doomed me, man!” As much as they fight against it, it is a beauty contest. It’s who you know, but I’d been there long enough. And so, finally one year – and I’m pretty sure there were four or five shakers and movers in the music industry who knew my work, who probably – I don’t know this – must’ve said, “If you’re gonna vote in this category, you gotta vote for this guy.” And then they call your name. But the first year I was nominated was the most exciting, it was the best because one of the hotels, where we stayed, was the center of activities – after the awards ceremony there was music in a half dozen different ballrooms for people in the “industry.” Arturo Sandoval and Celia Cruz were in one room, and BR549 was in another, and Herbie Hancock was playing music in another, and I thought, “Oh, my God, I’ve died and gone to heaven.” But with every year, every nomination, I saw the corporate business side more and more. You get an education in the music industry. But the odd thing is, we made less money the year after I won the Grammy. Both times. It did not increase my sales that much, and people stopped calling me ‘cause they just figured I was too expensive. I was getting paid five hundred bucks, seven hundred bucks, to show up in an elementary school for a day. That was [the way] I was making my living. And the elementary schools just stopped, like, “We can’t afford him. He won a Grammy!” It was like, NO! That Grammy was expensive! There were airplane tickets and hotel rooms and new dresses and… [laughter]. But, I’m lucky, it’s truly a calling card. The first year I won, friend of mine was there with me, and I was, predictably, already discounting why I got the award, and he said “Bill, they can’t take it away from you. It’s yours” So, it was very humbling. The first year, at the televised awards concert,, the evening concert, Ricky Martin was on stage playing “La Vida Loca” with a hundred drummers, and I was sitting next to Robert “Junior” Lockwood…

Rick & Allen: Wow!

Bill: …who had played with Robert Johnson. He played with Robert Johnson!

Allen: He’s purportedly the nephew of Robert Johnson.

Bill: And he was sitting there watching the show, with a look on his face like “What the hell is this?!” I said, “Mr. Lockwood, have you ever been to one of these?” He said, “Nope. And I’m never comin’ to another.” [laughter all around] So, you know, you had to be there.

Rick: Ah! You know, I believe you are our only two-time Grammy winner. Quite a few people have been nominated, and several have won [Vini Poncia, Tavares], but I think you are the only two-time winner. I’ll double check that, but it’s a calling card as well.

Bill: Actually, this year, an amazing thing happened. Three of the guys in the children’s category – three “white guys with guitars” – turned down the nomination because there were no people of color in the kid’s category [Reference to 2021 Grammy Best Children’s Album nomination controversy]. At our point, we were fighting to just have humans included in the children’s category [reference to Barney]. I haven’t been submitting. At a certain point I stopped submitting because…what’s one more to me? It’s gonna mean more to somebody else than it is to me.

Rick: The last thing I would like to ask about is the new album.

Bill: I’ll send you a link so you can hear it. It’s called Walking Each Other Home, and yeah, I’ve been working on it. I started – who knew? – I started working on it in 2017. It’s just, COVID, it has been just one thing after another. But it’s got great players on it. You know, Marty’s [Ballou, RIMHOF Inductee, 2015] on it, and Duke Levine’s on it, and this guy Lorne Entress, a really good drummer from Connecticut, and a bunch of guys Marty knows, including Sonny Barbato, who plays piano and organ and great accordion. Rachel Panitch, who plays fiddle with me. So, yeah, it’s a lot of songs I’ve had for years.

Rick: This is an adult album.

Bill: Yes, it is an adult album.

Rick: Folk songs or singer/songwriter…

Bill: Yeah, kind of Americana, although there’s a samba on it. We’ll do some promotion on it and hope it gets some airplay, and I can afford a cup of coffee. Promotion stuff has changed, and the album is currently being remixed! Again! Hopefully out in July [2021]…

BILL HARLEY DISCOGRAPHY:

ORIGINAL RELEASES

Compiled by Rick Bellaire

Round River Records releases series designations:

100 Series – Children’s Recordings

200 Series – Adult/Family/Folk Recordings

400 Series – Collaborations/Special Projects

500 Series – Video Releases

1984 Monsters In The Bathroom (Round River Records LP RRR-101)

1986 50 Ways To Fool Your Mother (Round River Records LP RRR-102)

1986 50 Ways To Fool Your Mother (Round River Records LP RRR-102)

1987 Dinosaurs Never Say Please (Round River Records Cassette RRR-103)

1987 Dinosaurs Never Say Please (Round River Records Cassette RRR-103) 1987 Cool In School (Round River Records Cassette RRR-104)

1987 Cool In School (Round River Records Cassette RRR-104)

1987 Coyote (Round River Records LP RRR-201)

1987 Coyote (Round River Records LP RRR-201)

Beginning in 1988, Bill Harley’s original releases on Round River appeared on CD with most titles also available on cassette for the next five years.

Beginning in 1988, Bill Harley’s original releases on Round River appeared on CD with most titles also available on cassette for the next five years.

1988 You’re In Trouble (Round River Records CD RRR-105)

1989 Peter Alsop & Bill Harley – In The Hospital (Moose School Records Cassette/Book #9)

1989 Peter Alsop & Bill Harley – In The Hospital (Moose School Records Cassette/Book #9)

1990 Come On Out & Play (Round River Records CD RRR-106)

1990 Come On Out & Play (Round River Records CD RRR-106)

1990 Grownups Are Strange (Round River Records CD RRR-107)

1990 Grownups Are Strange (Round River Records CD RRR-107)

1990 Bill Harley & Friends – I’m Gonna Let It Shine (Round River Records CD 401)

1990 Bill Harley & Friends – I’m Gonna Let It Shine (Round River Records CD 401)

1992 Who Made This Mess? (A&M Records VHS 83603-84143-0)

1992 Who Made This Mess? (A&M Records VHS 83603-84143-0)

Reissued in 1997 as Round River Records DVD RRR-501

1993 Big Big World (A&M Records Cassette & CD 31454-0073)

1993 Big Big World (A&M Records Cassette & CD 31454-0073)

Reissued in 1997 as Round River Records CD RRR-111 1994 Already Someplace Warm (Round River Records CD RRR-202)

1994 Already Someplace Warm (Round River Records CD RRR-202)

1995 Wacka Wacka Woo & Other Stuff (Round River Records CD RRR-108)

1995 Wacka Wacka Woo & Other Stuff (Round River Records CD RRR-108)

1995 From The Back Of The Bus (Round River Records CD RRR-109)

1995 From The Back Of The Bus (Round River Records CD RRR-109)

1995 Sitting On My Hands (Round River Records CD RRR-402)

1995 Sitting On My Hands (Round River Records CD RRR-402)

1996 Lunchroom Tales – A Natural History Of The Cafetorium (Round River Records CD RRR-110)

1996 Lunchroom Tales – A Natural History Of The Cafetorium (Round River Records CD RRR-110)

1997 There’s A Pea On My Plate (Round River Records CD RRR-112)

1997 There’s A Pea On My Plate (Round River Records CD RRR-112)

1998 Weezie And The Moonpies (Round River Records CD RRR-113)

1998 Weezie And The Moonpies (Round River Records CD RRR-113)

1999 The Battle Of The Mad Scientists And Other Tales Of Survival (Round River Records CD RRR-114)

1999 Play It Again – Favorite Songs & One New Story (Round River Records CD RRR-115)

1999 Play It Again – Favorite Songs & One New Story (Round River Records CD RRR-115)

2001 Down In The Backpack (Round River Records CD RRR-116)

2001 Down In The Backpack (Round River Records CD RRR-116)

2002 Carol Birch, Bill Harley & Angela Lloyd with David Holt – Sandburg Out Loud (August House Publishing CD)

2002 Carol Birch, Bill Harley & Angela Lloyd with David Holt – Sandburg Out Loud (August House Publishing CD)

2002 Mistakes Were Made – Live with Adults (Round River Records CD 203)

2002 Mistakes Were Made – Live with Adults (Round River Records CD 203)

2003 The Town Around The Bend – Bedtime Stories & Songs (Round River Records CD RRR-117)

2003 The Town Around The Bend – Bedtime Stories & Songs (Round River Records CD RRR-117)

2004 The Teachers’ Lounge (Round River Records CD RRR-118)

2004 The Teachers’ Lounge (Round River Records CD RRR-118)

2004 Various Artists inc. Bill Harley – cELLAbration! A Tribute To Ella Jenkins (Smithsonian Folkways CD 45059)

2004 Various Artists inc. Bill Harley – cELLAbration! A Tribute To Ella Jenkins (Smithsonian Folkways CD 45059)

2005 One More Time – More Favorite Songs And A New Story (Round River Records CD RRR-119)

2005 One More Time – More Favorite Songs And A New Story (Round River Records CD RRR-119)

2005 Blah Blah Blah (Round River Records CD RRR-120)

2005 Blah Blah Blah (Round River Records CD RRR-120)

2007 I Wanna Play (Round River Records CD RRR-121)

2007 I Wanna Play (Round River Records CD RRR-121)

2008 Yes To Running! Bill Harley Live (Round River Records CD RRR-122)

2008 Yes To Running! Bill Harley Live (Round River Records CD RRR-122) 2008 Yes To Running! Bill Harley Live (Round River Records DVD RRR-502D)

2008 Yes To Running! Bill Harley Live (Round River Records DVD RRR-502D) 2009 First Bird Call (Round River Records CD RRR-204)

2009 First Bird Call (Round River Records CD RRR-204)

2010 The Best Candy In The Whole World And Other Stories (Round River Records CD RRR-123)

2010 The Best Candy In The Whole World And Other Stories (Round River Records CD RRR-123)

2012 High Dive And Other Things That Could Have Happened… (Round River Records CD RRR-124)

2012 High Dive And Other Things That Could Have Happened… (Round River Records CD RRR-124)

2013 Bill Harley & Keith Munslow – It’s Not Fair To Me (Round River Records CD RRR-125)

2013 Bill Harley & Keith Munslow – It’s Not Fair To Me (Round River Records CD RRR-125)

2013 Nothing For Granted (Round River Records CD RRR-205)

2013 Nothing For Granted (Round River Records CD RRR-205)

2018 Further Around The Bend – More News From The Town Around The Bend (Round River Records CD RRR-126)

2018 Further Around The Bend – More News From The Town Around The Bend (Round River Records CD RRR-126)

2018 John Muir’s STICKEEN Told By Bill Harley (Round River Records CD RRR-127)

2018 John Muir’s STICKEEN Told By Bill Harley (Round River Records CD RRR-127) 2018 Same Moon – Bill Harley Live At Home (Round River Records CD RRR-206)

2018 Same Moon – Bill Harley Live At Home (Round River Records CD RRR-206)

LINKS AND RESOURCES

BILL HARLEY OFFICIAL WEBSITE

Excellent site constantly updated with all the latest news which has an invaluable Resources section with great ideas and information for families and educators.

https://www.billharley.com

MUSICIAN GUIDE BILL HARLEY BIOGRAPHY

Great, concise bio with information for more than a dozen sources for more info on Bill and his career written by Jeanne M. Lesinski.

https://musicianguide.com/biographies/1608000157/Bill-Harley.html

WIKIPEDIA PAGE FOR BILL HARLEY

Very thorough page with a bio, a discography, a complete bibliography and an extensive References section.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Harley