Wendy Carlos

WENDY CARLOS

Music Maker, Dreamer of Dreams

by Gerard Heroux

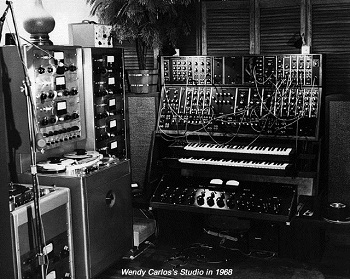

It’s hard to overstate the importance of Pawtucket-born Wendy Carlos’ work in the field of electronic music. From her time with Robert Moog in developing player-friendly interfaces for his Moog synthesizer, through her groundbreaking crossover classical albums created with her long time producer and musical collaborator Rachel Elkind, continuing on with her development of the Vocoder voice synthesizer as featured in the sound track to Stanley Kubrick’s film “A Clockwork Orange” and the seamless integration of electronic instruments and orchestral instruments as featured in the soundtrack to the Disney film “Tron,” Wendy has been in the vanguard of musical technology. The sound of music today, in both the popular and contemporary classical styles, would be far different without her distinctive melding of man and machine.

Wendy Carlos came into this world on November 14, 1939, and was named Walter by her parents because, in fact, she was born a boy. Walter studied piano and began composing music at an early age, and eventually, after high school, attended Brown University getting a degree in both music and physics. In the early 1960s Walter moved to New York, attending Columbia University for graduate work in music composition with electronic music pioneers Otto Luening (1900-1996) and Vladimir Ussachevsky (1911-1990)*. After graduate school Walter remained in the city to work with Moog and she has lived in New York ever since.

*Incidentally, Ussachevsky owned a farm in Shannock, RI and frequently resided there during the last two decades of his life.

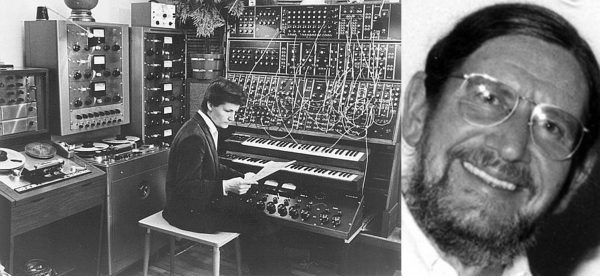

Walter Carlos (left) & Benjamin Folkman (right)

Walter Carlos (left) & Benjamin Folkman (right)

In 1964, Walter began her four-year association with Benjamin Folkman, a musician/musicologist who shared an interest in electronic music. Together they made various experimental recordings using the equipment at the Columbia University electronic music studio, including some arrangements of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750).

It was during the 1960s that Walter acted on her longtime realization that she was really a woman in a man’s body and she began taking hormone treatments in an effort to realign her body to her sexuality, eventually getting a full sex-change operation sometime in the early 1970s – the years of her greatest fame – legally changing her name from Walter to Wendy.

In 1966, Wendy (still known as Walter at that time) met Rachel Elkind, an aspiring jazz singer recently moved to New York City from San Francisco, who was working as an assistant to legendary CBS Records producer Goddard Lieberson. Rachel became interested in the J.S. Bach settings that Wendy and Benjamin had made with the newly modified Moog synthesizer. Rachel convinced Wendy that a full album of Bach’s music on the Moog would be a great introduction to electronic music for the general public and together they sold CBS on the idea as well.

Wendy Carlos (left) & Rachel Elkind (right)

Wendy Carlos (left) & Rachel Elkind (right)

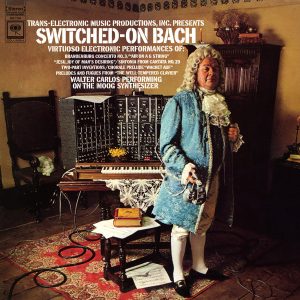

Wendy, Benjamin and Rachel then set up a creative partnership, Trans-Electronic Music Productions, Inc. (TEMPI) where Wendy and Benjamin provided the music, the technical know-how, and in Benjamin’s case, the historical-aesthetic perspective, while Rachel became the “ears,” encouraging the others to avoid merely imitating the sound of traditional instruments, encouraging them instead to create sounds unique to the Moog. What they created was a collection of arrangements that, in Benjamin’s words, were “musically expressive, electronically idiomatic, and spiritually and musicologically faithful to Bach.” The album, cleverly entitled “Switched-On Bach,” was released in 1968 and it proved to be a great success**, achieving “Gold” status for 500,000 units sold by the Recording Industry Association of America the following year, becoming one of the first “classical” albums to achieve that distinction.

** The back cover of the album prominently displays the following credit, “Electronic realizations and performances by Walter Carlos with the assistance of Benjamin Folkman.” In Benjamin’s liner notes, he implies that he played occasional supplemental keyboard parts, providing an “extra pair of hands and feet.” This, his musicological input, and the fact that he was working on some of this music with Wendy from four years earlier are what probably earned him the co-creator credit. While he wrote liner notes for several of the subsequent Carlos/Elkind releases, Benjamin pretty much faded out from TEMPI after “Switched-On Bach” and he was never again credited so prominently in any of its projects. Today he is known as a lecturer on music and is president of the Tcherepnin Society, an organization dedicated to the music of the 20th century Russian composer Alexander Tcherepnin.

Rachel’s vision of bringing electronic music to the masses had come true in spades. By 1969, “Switched-On Bach” was on Billboard Magazine’s Top 40 Albums chart and was a top ten album for a good part of that year, eventually winning three Grammy awards in 1970 for Best Classical Album, Best Classical Performance – Instrumental Soloist, and Best Engineered Classical Album. This success allowed Wendy and Rachel to set up a recording studio on the first floor of a New York West Side brownstone owned by Rachel and her mother. This building served as Wendy and Rachel’s home for the next 10 years where they created several more albums of synthesized classical music, as well as an album of original music composed by Wendy entitled “Sonic Seasonings.” Released in 1972, this album is structured around the four seasons of the year and is credited as being a precursor to today’s ambient/environmental music.

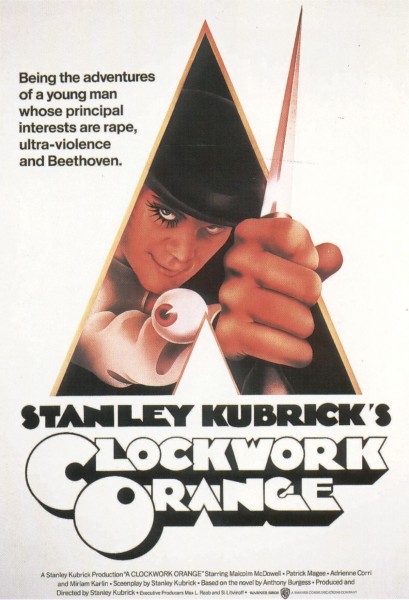

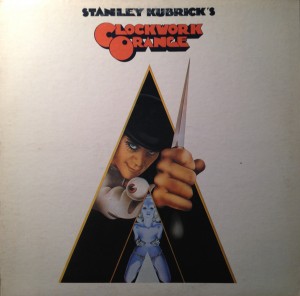

It was during the 1970s that Wendy and Rachel worked on movie soundtracks – most notably Stanley Kubrick ‘s 1971 film “A Clockwork Orange,” which focused on the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and featured Rachel ‘s singing voice synthesized through Wendy’s newly modified vocorder, a device created by Bell Laboratories in the mid 1960s that Wendy adapted for musical purposes. Especially useful in creating a robotic voice effects, the vocorder was widely used in 1980s pop music.

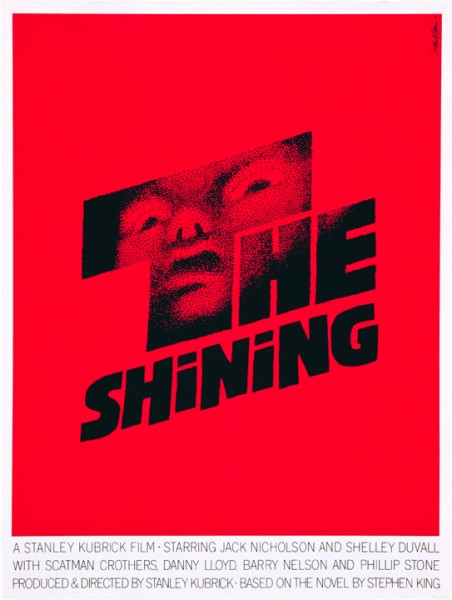

Wendy’s and Rachel’s final collaboration was another Kubrick soundtrack, 1980’s “The Shining,” and it is their only music together that credits Rachel as a co-composer with Wendy. (It turned out that Kubrick used very little of the music they composed for the film – using it primarily in the opening scenes.) It was around this time that Rachel fell in love and married a man, Yves Toure, and moved with him to France, thus ending one of the great, albeit unsung, partnerships in contemporary music. A partnership not unlike that of jazz greats Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, where one couldn’t tell where the ideas of one left off and the other’s began for much of their body of work.

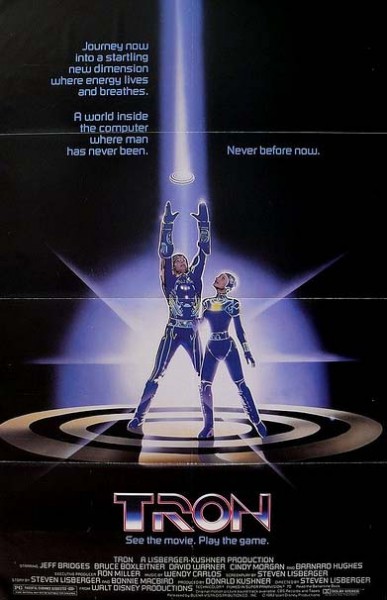

Since 1980, Wendy has continued producing albums of both original music (most notably the soundtrack to “Tron” in 1982) and classical arrangements using digital technology, including a parody of Sergei Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf” and Camille Saint-Saens’ “Carnival of the Animals” with musical funnyman “Weird” Al Yankovic for a 1988 children’s album.

She has worked during the early ’90s with fellow synthesizer artist Larry Fast in developing technology to restore old film soundtracks. In recent years she has been developing a new type of synthesizer called the WurliTzer II (sic), which combines pipe organ technology in a digital instrument for a more spontaneous performance capability.

Wendy and friend with the WurliTzer II in the background

As a composer, Wendy Carlos has, by her own admission, stood outside the world of contemporary classical music. She has performed only once as a synthesizer artist, playing selections from “Switched-On Bach” with the Saint Louis Symphony in a 1969 concert. She has never been a professor at a university, and beyond writing a concerto for string quartet and orchestra for the Kronos Quartet, she has had very few commissions from classical music ensembles. Just out of graduate school in the early 1960s, she bucked the trend of writing difficult music primarily for other composers. Her interest in melody and clear musical form, combined with the infinite combinations of tone color available from the Moog, led her to the music of J.S. Bach (that plus the fact that the limited expressive capabilities of the early Moog instruments steered Wendy away from composers of Romantic and Impressionistic music). Yet her albums were looked down upon by the Baroque and Early Music purists of the period. Her aesthetic was closer to that of the minimalist composers such as Phillip Glass and Terry Riley – music with feet in both the classical and popular camps. Yet Wendy’s success seemed to keep her at arms length from the downtown underground art scene that supported such composers, despite her being a long time Manhattan resident.

Much of this estrangement was in no doubt due to the struggles Wendy had with her own sexuality, and the steps she took to overcome her unbalanced life certainly put her out of the norms of 1970s social convention. Over the years, she has taken efforts to protect her image when necessary, famously suing pop musician Momus in the late 1990s for what she deemed offensive content in his song “Walter Carlos.” Yet she is, by most accounts, open and friendly to interviewers and helpful to all who will accept her on her own terms. And as others have followed her lead, changing from a Walter to a Wendy is less shocking now than is was 40 years ago.

Wendy Carlos’ life can best be described as a series of obstacles, which through a combination of ingenuity, perseverance and good timing, she overcame for the benefit of contemporary music (although the synthesizer has been blamed for putting orchestral musicians out of work, especially in theatrical productions). Yet how much of her success can be credited to her early years in Rhode Island is hard to say. As Wendy states in a page from her website: “It’s of very little daily concern to me that I was born and brought up in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, although I’m not ashamed of being from that sleepy small city just north of Providence.” Whatever the source, Wendy Carlos has proven to be someone who believes, as Robert F. Kennedy did, that there are those who look at things the way they are and ask, “Why?” – and there are those, like herself, who dream of things that never were and ask, “Why not?”

LINKS AND RESOURCES

Wendy Carlos – Official Website:

http://www.wendycarlos.com

Moog Music – the official site’s page about early synthesizers:

http://www.moogmusic.com/legacy

People Magazine article:

http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20091206,00.html

Last.FM posting – Wendy Carlos & Rachel Elkind + Wikipedia entry:

http://www.last.fm/music/Wendy+Carlos+&+Rachel+Elkind/+wiki

National Public Radio: A great interview with Wendy for NPR:

http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/features/interview_carlos.html

A short film clip with Wendy talking about the instrument used in her music for Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining:

http://vimeo.com/43222377

http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/sk/page22a.htm

A short BBC TV introduction to the Moog synthesizer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=usl_TvIFtG0

A wide ranging 2007 conversation with Wendy for New Music Box website:

http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/wendys-world/

WENDY CARLOS DISCOGRAPHY: ORIGINAL RELEASES

Compiled by Rick Bellaire

All of the below albums with the exception of the Vox Turnabout and Moog demonstration LPs have been reissued on CD beginning in the mid-1980s. Most are still in print as of this writing (2012) and most are available as downloads from iTunes, Amazon and other internet outlets

WALTER CARLOS LPs

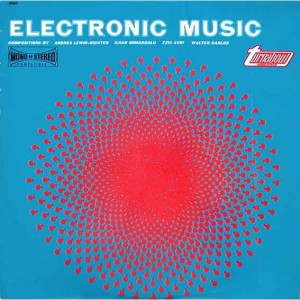

Electronic Music (Vox Turnabout TV-34004) 1965

Various artists collection; includes two compositions by Carlos – her first released recordings

Various artists collection; includes two compositions by Carlos – her first released recordings

Moog 900 Series – Electronic Music Systems (R.A. Moog RMD-100) 1967

Promotional demonstration disc (10″ LP distributed in a plain, white sleeve) displaying the capabilities of the first commercially available Moog synthesizer recorded while Carlos was working as an recording engineer at Gotham Recorders in New York City and consulting with Moog on ways to make the synthsizer more “user-friendly” – more a musical instrument than a machine

Promotional demonstration disc (10″ LP distributed in a plain, white sleeve) displaying the capabilities of the first commercially available Moog synthesizer recorded while Carlos was working as an recording engineer at Gotham Recorders in New York City and consulting with Moog on ways to make the synthsizer more “user-friendly” – more a musical instrument than a machine

Listen to this historic recording by clicking the link below:

Moog 900 Series Demo Record

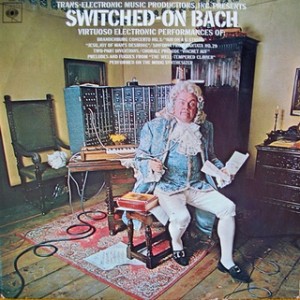

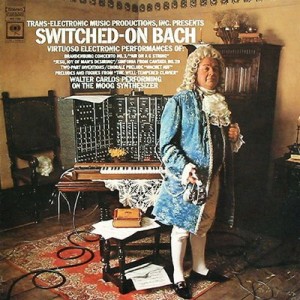

Switched-On Bach (Columbia Masterworks MS-7194)1968

Very rare and collectable first pressing showing “Bach” seated. Carlos and her producer objected to the image as “clownish” and “trivializing” and the cover was immediately changed for all future pressings to the well-known image of the man standing as seen below

The first classical album to sell 500,000 copies and be honored with the Gold Record Award by the Recording Industry Association of America. The LP went on to win three Grammys including “Best Classical Album”

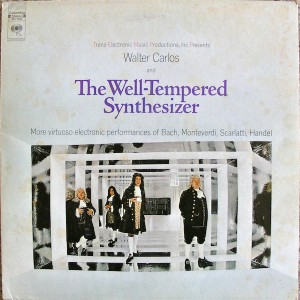

The Well-Tempered Synthesizer (Columbia Masterworks MS-7286) 1969

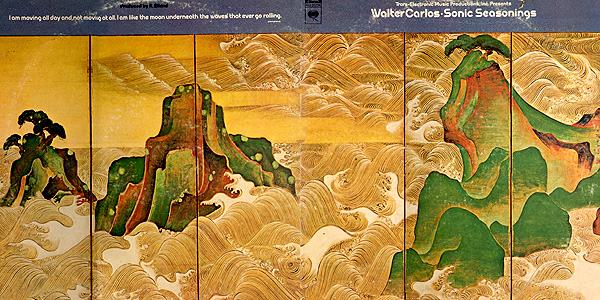

Sonic Seasonings (Columbia KG-31234 2xLP) 1972

Sonic Seasonings (Columbia KG-31234 2xLP) 1972

Gatefold sleeve for this double LP opened up to display the full painting by 17th century Japanese painter Ogata Korin

A Clockwork Orange – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (Warner Bros. BS-2573) 1972

Various artists collection featuring Carlos’ themes along with other classical recordings utilized in the movie and Gene Kelly’s “Singin’ In The Rain”

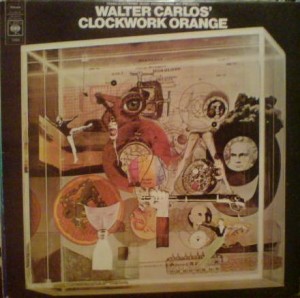

Walter Carlos’ Clockwork Orange (Columbia KC-31480) 1972

The complete score – all the music composed or realized for the film

The complete score – all the music composed or realized for the film

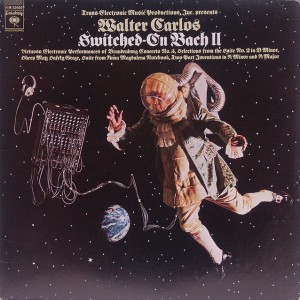

Switched-On Bach II (Columbia KM-32659) 1973

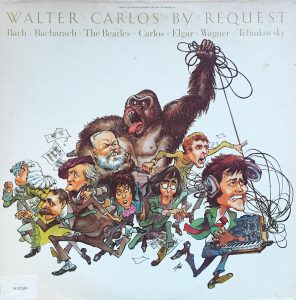

By Request (Columbia Masterworks M-32088) 1975

By Request (Columbia Masterworks M-32088) 1975

All of the above Columbia albums were reissued as by “Wendy Carlos” after the release of the below album

WENDY CARLOS LPs

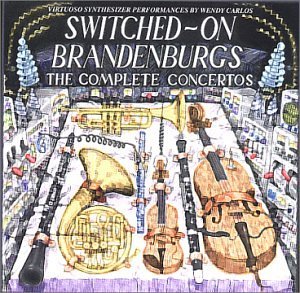

Switched-On Brandenburgs (Columbia Masterworks M2x-35896) 1979

The Shining – Score Selections from the Soundtrack (Warner Bros. HS-3449) 1980

The Shining – Score Selections from the Soundtrack (Warner Bros. HS-3449) 1980

Tron – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (CBS SM-37782) 1982

Tron – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (CBS SM-37782) 1982

WENDY CARLOS CDs

WENDY CARLOS CDs

Digital Moonscapes (CBS Masterworks M-39340) 1984

Beauty In the Beast (Audio SYN-200) 1986

Beauty In the Beast (Audio SYN-200) 1986

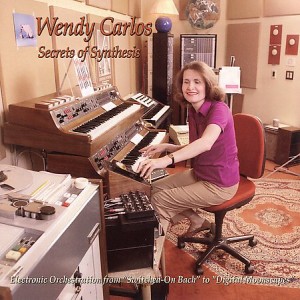

Secrets of Synthesis (CBS Masterworks MK-42333) 1987

Peter and the Wolf/Carnival Of The Animals with “Weird Al” Yankovic (CBS MK-44567) 1988

Peter and the Wolf/Carnival Of The Animals with “Weird Al” Yankovic (CBS MK-44567) 1988

Switched-On Bach 2000 (Telarc CD-80323) 1992

Switched-On Bach 2000 (Telarc CD-80323) 1992

Tales of Heaven and Hell (East Side Digital ESD-81352) 1998

Tales of Heaven and Hell (East Side Digital ESD-81352) 1998

Switched-On Boxed Set (East Side Digital ESD-81422) 1999

Switched-On Boxed Set (East Side Digital ESD-81422) 1999

4 CD compilation of Switched-On Bach, The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, Switched-On Bach II and Switched-On Brandenburgs with a lavish 144-page book)

4 CD compilation of Switched-On Bach, The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, Switched-On Bach II and Switched-On Brandenburgs with a lavish 144-page book)

Rediscovering Lost Scores, Volume 1 (East Side Digital ESD-81752) 2005

Compiles previously unreleased music from The Shining, A Clockwork Orange and several UNICEF films

Compiles previously unreleased music from The Shining, A Clockwork Orange and several UNICEF films

Rediscovering Lost Scores, Volume 2 (East Side Digital ESD-81762) 2005

Compiles previously unreleased music from The Shining, Tron, Split Second, Woundings and 2 Dolby demonstration tracks.

Compiles previously unreleased music from The Shining, Tron, Split Second, Woundings and 2 Dolby demonstration tracks.