Francis Madeira

2014 INDUCTEE

Classical

FRANCIS MADEIRA

(1917-2017)

The Master Builder of the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra

by Gerard Heroux

How does one go about starting a symphony orchestra? Once the sheet music is bought and the musicians are hired, once the performance venue is secured with times and places for rehearsals settled upon, and once the ticket prices and all details are announced, what’s next? Well, for the young Francis Madeira, who upon discovering that the Ocean State had no professional orchestra active in the area, it was obvious – he would somehow bring symphonic music to Rhode Island audiences as an orchestral music director.

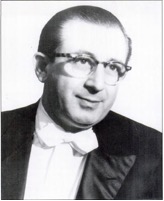

Yes, even with the basic components in place, a musical organization can only take flight with someone as its pilot, and that someone is the music director – the one who chooses the music, auditions the players, organizes the rehearsals, and ultimately decides the musical vision for both the performance itself and for the group as a whole, Whether he or she leads by standing in front of the ensemble waving a conductor’s baton or whether he or she leads while playing in the group, the music director is an essential element for groups beyond 10 or 12 players in size. The music director as conductor needs to know the music inside and out – every part – and works to mold the players’ talents to the intentions of the composer. He or she will convey that knowledge to the musicians though facial expressions, body language, specific beat patterns, and cuing gestures. And by 1945 Francis Madeira’s would indeed be doing all of that by waving his baton in front of a group of his own – as music director of the soon to be named Rhode Island Philharmonic, an activity that dominated his professional life until his retirement in 1978.

A multi-exposure shot of Francis Madeira in his later years conducting a RI Philharmonic rehearsal – from a Providence Journal feature article.

A combination of talent, excellent training and sheer good luck put Madeira in a position to start the R.I. Philharmonic. That he succeeded as well as he did, leading the organization for 38 years and in the process becoming a fixture in the state’s cultural landscape, is a testament to his ability for networking with potential patrons, inspiring them to get involved in support of classical music. It’s worth noting that all this came to be in a place where he was not a native son (Madeira was born in 1917, in Jenkintown, PA and grew up in the Philadelphia area), so he couldn’t rely on any family connections or friends to help ease the way. This speaks to the man’s drive and determination.

Like many musicians Francis King Carey Madeira (he was named after his maternal grandfather) started off playing piano as a young child. His father, Percy Childs Madeira, Jr., was a man of many hats including coal merchant (the family business), lawyer, banker and well-respected amateur archeologist, and his mother Margaret Carey Madeira, managed the household and in later years was an advocate for mental health reform, chairing the National Mental Health Foundation. Indeed the Madeiras wanted only the best for their three children (Percy, Francis and Eleanor – in that order), and encouraged primarily by his mother, young Francis received piano lessons from local teachers Luther Conradi and Mary Virginia David. In time he was enrolled into the prestigious Avon Old Farms School, an all-boys college preparatory boarding school in Avon, Connecticut where he continued his piano studies, traveling to study with teachers in Hartford.

After graduating from Avon Old Farms in 1934 young Francis set his sights on a career in music, and with a living allowance from his family he tried to make a go of it as a classical pianist. Finding he needed more technique Madeira took three years of piano lessons in New York City at the apartment of Wager Swayne, an American-born teacher with an international reputation who taught for many years in both Vienna and Paris. No doubt Madeira would have been aware of Swayne because one of his previous teachers, Mary Virginia David, was herself a pupil of Swayne.

Madeira found Swayne to be an excellent instructor and after three years he became confident enough to audition before the piano faculty of what was then known as The Juilliard Graduate School of Music, a place Madeira hadn’t heard about until he started studying with Swayne. Interestingly Juilliard was not really a graduate school at the time, at least not in the formal sense, but rather it was more of a professional training school for students who could function at a very high level regardless if they graduated from college or high school (as in Madeira’s case). In effect this meant that he never attended a four year college to earn a baccalaureate degree in music.

Upon passing his audition at Juilliard in 1937, Madeira was assigned to the Texas-born virtuoso Olga Samaroff. Studying with Samaroff was quite a feather in Madeira’s cap. In the early years of the 20th century she was considered one of the great classical pianists on either side of the Atlantic. And she was something of a celebrity being the ex-wife of Leopold Stokowski, the famed conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra (and real-life musical “star” of the Disney movie Fantasia). In 1923, however, she had gone through a bitter divorce from Stokowski from which she never recovered emotionally coupled with an accidental fall that did damage to her shoulder. By the time Madeira was her pupil she had pretty much put her performing career behind her, dedicating herself more and more to her piano students at both Juilliard and the Philadelphia Conservatory.

By his third year of lessons it became obvious to Samaroff that Madeira was showing more of an interest in the expressive content of his music assignments than he had for the technical aspects of piano performance. And while he would eventually prove in his post Juilliard career to be a sensitive accompanist and a capable contributor in small group settings, Samaroff sensed that Madeira did not have what it took to be a topflight concert pianist. Instead she encouraged her pupil to consider music conducting for a career. During her time as an active performer Samaroff used her considerable star power to promote the careers of unknown conductors – including that of Stokowski (her second husband) – so her opinions in this matter were not to be taken lightly. After serious consideration, Madeira took her suggestion, applied and was accepted into the intensive three year conducting fellowship at Juilliard that was overseen by Albert Stoessel, the director of the school’s orchestra and opera program.

Madeira found his true musical calling in this program and upon completion of his studies in the spring of 1943 he was awarded his artist certificate in conducting – right in the middle of World War II. Since he was exempt from military service he was able to start searching for a music position right away. The career placement office at Juilliard wanted to send Madeira to a conducting position at Hendrix College, Arkansas, which at the time had a close association with the school. He refused the position however when he realized that there would be other required duties beyond directing the college orchestra, such as giving instrumental lessons to the band students for which he had no training. Madeira was despairing of finding suitable work in music when he heard about a temporary position at Brown University for the fall 1943 semester. With this opportunity in mind he perused the national bookings issue of “Musical Times” magazine to see what Providence had to offer a young musician like himself. He discovered that there was no professional orchestra currently active in the area so he decided, “That’s where I have to go!”

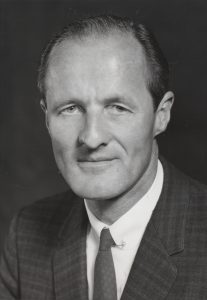

Henry Merrit Wriston (1889-1978), the man who gave Francis Madeira the chance to teach at Brown University (from a 1957 painting by John Lavalle).

Madeira took an interview with Arlan Coolidge, the head of the Music Department at Brown, and passing that, was interviewed by the university president Henry Merritt Wriston. He subsequently was offered the position of Instructor in Music for the 1943-1944 academic year. He found out years later that he clinched getting the job with his honest admission to Wriston that he didn’t necessarily see himself as staying on at Brown for the rest of his career. But, ironically enough, that’s pretty much how it turned out as the temporary position carried over into the next year and continued on for more than twenty years after that. From the very first he assumed the directorship of the Brown-Pembroke student orchestra and for the first 6 years he taught various classes such as music theory and music appreciation until Henry Wriston gave him an extended leave in the Fall of 1950 allowing Madeira to concentrate on running the RI Philharmonic and to perform professionally as piano accompanist for his wife, the great American contralto Jean Madeira.

Francis Madeira resumed his teaching duties at Brown in 1953, but he turned over the directorship of the Brown orchestra to another Brown music professor, violist Martin Fischer who was also Madeira’s assistant conductor at the RI Phil. Madeira’s academic career at Brown eventually led to his being named an Associate Professor in Music, the title he retired with in 1966.

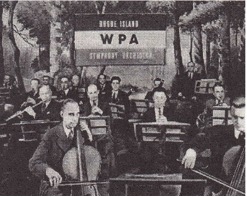

But that was all in Madeira’s future. Things weren’t so certain in 1943, when he arrived in Providence to start his one-year appointment at Brown. So he started making inquiries into conducting opportunities beyond those at the university. He already knew from his research that there was no professional symphony orchestra active in the area – the erstwhile Providence Symphony having ceased operations at the outset of the war – and finding no support for reviving the earlier group the idea eventually came to him that he might test the waters with a newly formed small group of musicians for a limited number of concerts at various locations in the state. This idea while totally original to Madeira had actually already been put into practice the previous decade in various communities throughout the country by the touring orchestras of the Works Progress Administration’s federally funded music program – of which the short-lived Rhode Island Music Project orchestra was the local exemplar.

The Works Progress Administration’s Rhode Island Music Project Symphony Orchestra performing during the 1930s.

It took about a year and a half for Madeira’s vision to become a reality, gaining financial support from classical music lovers in the RI business community – some of whom were parents of his Brown University music students. A loose group of supporters formed around Madeira’s leadership and musicians were contracted with the help of Everard Appleton, an attorney and amateur violist who eventually chaired a formal RI Philharmonic committee and helped draft its bylaws. Appleton recommended many local musicians to Madeira for the original roster of the newly named Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra. Many of these musicians stayed with the orchestra in the years that followed, with Madeira holding auditions to replace members as they left the group – as opposed to auditioning members regularly to keep the quality high. The change in this policy in later years was a source of conflict in the organization as the need became evident to move the Philharmonic to the next level musically.

By late spring 1945 World War II was rapidly coming to a halt. Germany had surrendered and America began to focus its attention on the war in the Pacific. There was a distinct sense that the fighting would be over soon. This in turn led to a more positive outlook regarding cultural activities – such as launching a classical music series in a small state like Rhode Island. Sensing this elevated feeling, the Philharmonic organizers, which besides Madeira and Appleton included Albert Noelte a local industrialist, Arlan Coolidge of Brown’s Music Department and Irene Mulick from the RI Federation of Music Clubs, announced an ambitious program of 16 concerts in 6 locations throughout the state. The first tour agreed upon was for mid November, and Madeira got Brown University to grant him sabbatical for the semester. A site for the first concert was chosen in the town of Westerly – about as far as one could get away from Providence and still be in Rhode Island. Perhaps the thought was to showcase the group out of town, work out a few kinks and if all went well enjoy the benefit of a publicity “buzz” for a “big city” opening.

However as November approached it appeared that perhaps the time wasn’t right after all because advance ticket sales did not look promising. But Albert Noelte encouraged Madeira to stay the course. Noelte called for several meetings and within a 5 day span selling committees went to work getting the word out and the money in. And as it so happened – in spite of a heavy rainstorm – the first RI Philharmonic concert played to a decent house on November 14 in the Westerly High School auditorium with politicians and community leaders in attendance (including the newly elected governor, John O. Pastore who addressed the audience and welcomed the orchestra to the R.I. musical scene) for a program of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Bizet and Johann Strauss, Jr.

The tour continued – first to State College (now URI) in Kingston, then Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Westerly (again), Newport and finally Providence (at the Rhode Island School of Design auditorium). The reception for this was encouraging and plans were made to continue the series over a two-week periods in February and April of the following year. With financial backing in place, the newly named Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra continued its inaugural season of concerts with a slightly reduced schedule from the original plans of the year before, the State College venue was eliminated from the tour schedule due to poor turnout. All told the momentum was there to keep the ball rolling for the next series in the Fall of 1946, and with some peaks and valleys, continuing onward through the years until the present time.

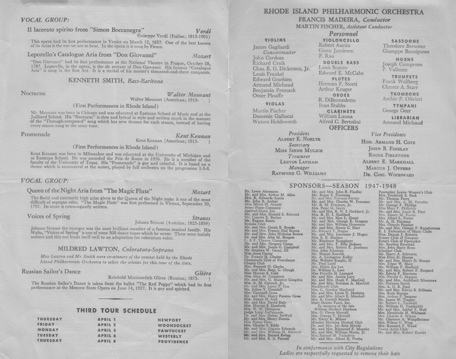

A program from the RI Philharmonic’s third season of concert tours. This tour is notable for its presentation of four works by living composers – three of which are American. Madeira frequently programmed contemporary works throughout his time with the Philharmonic.

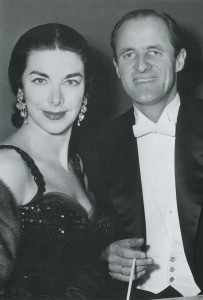

Besides being the start for the orchestra he created, Madeira had good reason to be especially fond of these first concerts because they featured a fellow Juilliard alumna, contralto Jean Browning, in a program of operatic selections. They had known each other at Juilliard and that friendship had by now turned to romance and within a couple of years Madeira would marry Browning in June of 1947. Taking her husband’s name, Jean Madeira would eventually have the better-known career with several recordings to her credit and frequent appearances at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

The yearly statewide itinerary for the Philharmonic continued for a few years until 1952 when the orchestra found a permanent home at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium, located on Smith Hill beside the RI State House. From that point on there were fewer out-or-town performances until the establishment later in the decade of a pops orchestra that would play outdoors in the summer months. Also by this time Madeira had established an audition policy for determining first chair players and for accepting new orchestra members.

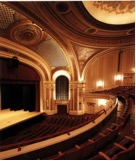

An interior view of the Veterans Memorial Auditorium, the first permanent home of the RI Philharmonic Orchestra.

No orchestra can continue to draw an audience by playing only symphonies, suites and overtures. People want to connect with a single musician whose charisma and virtuosity can be framed and supported by the larger group. For a music director this means programming concertos – typically concertos for the more brilliant instruments like violin or piano – or programming operatic selections. Madeira did both almost from the very start and through the years the Philharmonic has managed to bring in such world class soloists as the pianists Gary Graffman, Claudio Arrau, Ruggerio Ricci, Leon Fleischer and Gina Bachauer, the violinists Isaac Stern and Jaime Laredo and opera stars like Rhode Island’s own Eileen Farrell. And while finances were always a struggle to maintain (as they still are today), the Philharmonic managed to double its subscriptions from 850 in 1950 to 1,750 in 1953 (the group’s second year at the Veterans Auditorium) which surely reflects Madeira’s skill in programming as well as the musical quality of his ensemble.

Raymond Jackson, international concert pianist and Rhode Island native who performed under Madeira with the RI Philharmonic as a child prodigy in the late 1940s, seen here in 1947, age 14.

An orchestra also needs to build its audience by reaching out to school children, the Philharmonic organization realized this and formed a Children’s Concert Committee. By the early 1950s Madeira began to program special concerts designed to be appreciated by younger audiences where students would be bussed into Veterans Auditorium or some other large venue to hear the Philharmonic play. These outreach performances continued throughout Madeira’s time as music director but have in recent times been pretty much discontinued due to shrinking school budgets and the increased emphasis on test preparation for meeting stricter state and federal educational standards, limiting time for in-school non-academic activities.

By 1954 a need was recognized for building the future of the orchestra from the other end, namely the training of young musicians in an orchestral setting. Irene Mulick, the Philharmonic president at that time, brought the idea to Madeira and he saw value in the proposal, chairing an exploratory committee for forming a youth orchestra. The committee chose someone from within the organization to direct the new ensemble, namely Joseph Conte, the RI Philharmonic’s first chair 1st violinist and concertmaster (since 1949), who had a background in music education. The RI Philharmonic Youth Orchestra (RIPYO) was open to young instrumentalists of a wide range of ages – from 8 years old to 18 – the only requirements were for the students to be taking private lessons on their instruments and they had to pass a brief audition.

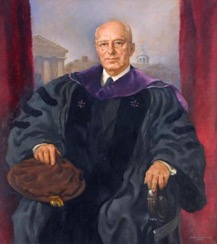

Dr. Joseph Conte (1914-2001), for 21 years concertmaster of the RI Philharmonic and the first director of its youth orchestra (RIPYO).

Rehearsals for the youth orchestra were held in the auditorium of the Providence Journal Bulletin building and the first concert was given in 1956 at the Rhode Island School of Design auditorium. The group was so successful that eventually it would be divided into junior and senior orchestras, giving its concerts at Veterans Auditorium and, for the senior group, at various schools throughout the state. Conte and Madeira worked out an apprenticeship program where the most talented students could win a seat in the parent orchestra, playing in all the rehearsals for a year and getting the opportunity to audition for permanent spots as openings occurred.

Joseph Conte’s main position within the RIPO organization, however, was that of concertmaster, and a word or two describing that position may help explain the course of events that transpired after he became the director of RIPYO. The concertmaster of any symphony orchestra is next in line after the music director in determining the musical result of the ensemble. By tradition the first chair player of the 1st violins sits immediately to the left of the conductor, he or she coordinates the articulation of phrasing and bow direction for the string section of the ensemble during rehearsals and is in essence the one who gets the orchestra in tune just before the conductor comes out to start the concert. The concertmaster helps translate the conductor’s musical vision to the rest of the orchestra and in some cases the concertmaster is named the assistant music director though that has not been the case for the RI Philharmonic. In some orchestras the concertmaster is more like a union shop steward, a spokesman for the rest of the musicians if problems arise. It was in this capacity that Joseph Conte moved from being a close partner with Francis Madeira to something more like an adversary.

Indeed by the orchestra’s 10th anniversary concert in 1955 the Rhode Island Philharmonic was truly a group of talented professionals playing the standard classical repertoire plus more adventuresome fare. The program for this event makes this evident: Mozart’s Overture to “The Marriage of Figaro,” Beethoven’s Symphony no.7, the Rhode Island premier of Francis Poulenc’s Concerto in D minor for Two Pianos and Orchestra – with soloists Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, concluding with three selections from Hector Berlioz’s “The Damnation of Faust.” Like the very first concert in 1945, a formal greeting to the audience was given, this time by Governor Dennis J. Roberts.

For its fifteenth anniversary concert in 1960 the orchestra continued to show progress as an ensemble, confidently taking on the larger works in the repertoire such as Ludwig van Beethoven’s famous 9th symphony for vocal soloists, chorus and orchestra, which on this occasion was given with the assistance of the Lexington Choral Society, Allen C. Lannom director. Madeira re-visited Beethoven’s Ninth ten years later for the 25th anniversary concert, this time with Community Chorus of Westerly, George Kent director.

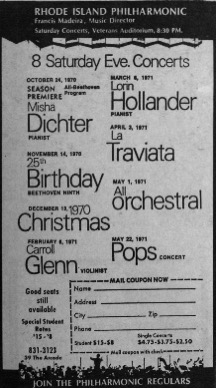

An advertisement in the Providence College student newspaper shows the high quality programming marking the orchestra’s 25th anniversary season. Note the ticket prices for students on the mail-in coupon in the lower right corner, $8-$15 for a full season and $2.50-$4.75 for single concerts. Incidentally, the current season subscription for college students is still very reasonable at $25 for all concerts and open rehearsals!

Throughout all this time Madeira had been loyal to those who stuck by him in the early years, but as openings occurred he wished to hire the best available as replacements, typically freelance musicians from the Boston area. This put him in conflict with Conte as union president who felt that the RI Philharmonic should be hiring from the local talent pool. Conte saw the group as being a very good community orchestra, by name limited to Rhode Island musicians, while Madeira’s goal was for something higher, developing the RI Philharmonic into a reputable regional orchestra.

With this tension in the background the 1960s brought further changes to the organization, much of it for the good. The orchestra started to present “pops” programs similar to that of the famous Boston Pops, featuring orchestral arrangements of Broadway show tunes and other popular music of the day mixed with light classics. There’d typically be one such concert at the end of the regular season in May plus a few outdoor concerts during the summer in places like the quadrangle at Brown University or Narragansett Town Beach. These might be conducted by Madeira or one his conducting assistants. Erich Kunzel, Madeira’s assistant in the mid 1960s, became a specialist in Pops programming and went on to fame as the conductor of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra.

Continuing the tradition established by Francis Madeira, the RI Philharmonic Pops Orchestra performs at a 2011 Fourth of July concert at India Point Park, Providence under the direction of resident conductor Francisco Noya, an assistant to current music director Larry Rachleff.

By the mid ’60s the orchestra gained a more secure financial footing with major fundraising drives to qualify for federal and state matching grants, plus donations that contributed toward a permanent endowment fund. There were professional achievements for Madeira during these years, having retired from his teaching duties at Brown in 1966. He concertized as a collaborative pianist with his wife Jean for voice recitals, and took on guest conducting engagements in orchestras across the U.S. and abroad.

The financial gains made by the RI Philharmonic during the 1960s were more for the long term however, because the day-to-day cash flow was still a major concern for the organization. And adding to this was pressure from the musicians for an increase in pay and better working conditions. Both sides were in agreement that the pay was indeed lower than it should have been, but how much could the orchestra afford and according to what pay scale should any increase be distributed were some of the issues. An agreement was eventually reached but not after a certain amount of acrimony between Joseph Conte and the Philharmonic board of directors.

By late Summer of 1969 the situation had deteriorated despite mediation efforts from Madeira, and Conte resigned as concertmaster and director of RIPYO, taking about a third of the RIPYO students with him to start a new group, the Young People’s Symphony Orchestra of Rhode Island (YPSORI), which continued in various capacities under Conte’s direction until his retirement in the late 1990s. Madeira’s acceptance letter of Conte’s resignation speaks with affection of their long term relationship, “It is not possible to express the full extent of my regret at your departure…I bear no rancor with regard to any difference of opinion.” It was during this time after his departure from RIPO that Conte became head of the Providence local of the American Federation of Musicians, seemingly cemented in his opposition to the RI Philharmonic board of directors.

The new decade brought further changes for Madeira and the RI Philharmonic, not the least of which was the death of Jean Madeira in 1972. The loss of his life partner and emotional confidant certainly made the music director’s struggles in leading the orchestra a harder burden to bear and quite possibly colored how Madeira saw his future with the orchestra. After Joseph Conte’s departure a new concertmaster was appointed in Barbara Barstow, and Martin Fischer was appointed to lead the youth orchestra.

Barbara Barstow (1917-2011), RIPO concertmaster after the departure of Joseph Conte and one of the few women concertmasters of her day.

Martin Fischer (1916-2011) in his later years, the first Assistant Conductor of the RI Philharmonic

and Conte’s replacement as conductor of RIPYO.

Subscriptions were increasing but it became apparent that the limited parking and poor condition of the facilities at Veterans Auditorium were putting a cap on attendance at Philharmonic concerts, so the board of directors began investigating the possibility of finding a new home for the orchestra. This was pursued through the rest of the 1970s but wasn’t accomplished until well after Madeira’s retirement when the orchestra relocated for a 10 year period in the mid-1980s to the larger Loew’s Theater on Weybosset Street, downtown Providence. This early 20th century movie palace had been newly refurbished in the early 1980s and re-named the Providence Performing Arts Center (PPAC), but the natural sound of the orchestra didn’t carry well there and the orchestra returned to the superior acoustics of a spruced up Veterans Auditorium in the mid-1990s.

Despite the bad conditions at Vets and the occasional flare-ups with the musicians’ union, the RI Philharmonic continued to improve musically under Madeira’s leadership during the 1970s. So much so in fact, that the Boston Symphony Orchestra no longer felt the need to include Rhode Island on it’s yearly outreach tours of New England communities. The musicianship had improved to the point where Madeira felt he could program works that RI classical music lovers would previously have had to travel to Boston or New York to hear. For example, during the 1970s Madeira lead the group in a cycle of the massive symphonies of Gustav Mahler, works that extend beyond Beethoven’s 9th in scope and difficulty, some of which require large orchestras with vocal soloists and chourses. The Chorus of Westerly, RI a high quality community choral group under the directorship of George Kent – who was also Madeira’s assistant conductor at the RI Philharmonic – supplemented the orchestra for these and other large choral/symphonic works. Sometimes the whole orchestra was hired for national touring companies of opera and ballet to play in the pit for their Providence stops, this too is a reflection of the increased level of musicianship at the Philharmonic during this time.

By early 1978, however, Madeira realized that he was developing a bothersome hearing loss and he announced his immanent retirement as director of RIPO. In May of that year he achieved a homecoming of sorts when he conducted the Juilliard Orchestra in New York and by June, Madeira completed his long fruitful term with the R.I. Philharmonic with a farewell concert concluding his Mahler cycle. The next season involved the promotion of George Kent to a new position as Associate Conductor, and saw the auditioning of potential new music directors to lead the orchestra into the next decade.

A successor was finally selected in 1979 from among the half dozen talented applicants. Alvaro Cassuto of the National Portuguese Radio Symphony Orchestra would take over the reins, and moved Providence where he resided for much of the year. But unlike his predecessor, Cassuto wouldn’t be a full-time conductor of the RI Philharmonic. He took the RIPO position conditional on his ability to keep conducting the Portuguese Radio Symphony. The Philharmonic board accepted this condition as they did similarly for every RIPO conductor since, and Cassuto maintained the two positions traveling frequently between Providence and Lisbon.

Among modern symphony orchestra conductors, Francis Madeira was perhaps the last of his breed, someone who started a group from scratch and stayed with that group for his entire career. Since his retirement he has been living in Maine, the state where he and Jean had a retirement home and a convenient location for his outdoor hobbies of cross country skiing and high altitude hiking. For a few years after retirement he went back to playing the piano, even performing as a soloist with the RI Philharmonic Youth Orchestra in the piano concerto of Robert Schumann at Veteran’s Auditorium in 1984. He has also been active in cultural stewardship, serving on the Maine State Arts Commission.

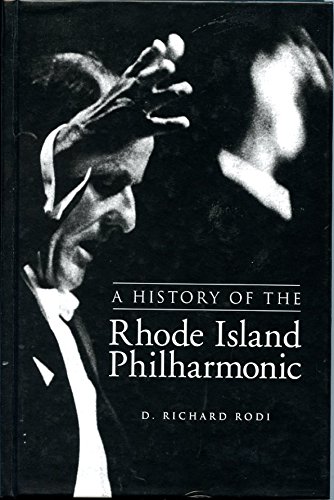

Cover image of the only book on Madeira and the RI Philharmonic authored by a former president of the Philharmonic board of directors, D. Richard Rodi.

He has also served on the advisory board at Avon Old Farms School where he was honored with a Distinguished Alumni Award in 2010 (an award he shares with the late folk singer Pete Seeger who graduated from Avon Old Farms in 1936, a couple of years after Madeira). He received honorary degrees from Providence College, Rhode Island College and Brown University. Other awards include: The RI Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, 1972; The John F. Kennedy Award for Service to the Community, 1978; The Citizen Citation Award from the Mayor of Providence, 2003; and most recently his 2014 induction into the RI Music Hall of Fame. And in honor of his work with young musicians there is a Brown Alumni Association scholarship for talented music students named for him and his wife – the Jean and Francis Madeira Award.

May, 2014: Francis Madeira receiving his RI Music Hall of Fame award from RIMHOF secretary James Toomey.

In recent years, contemplating a life well led, Maestro Madeira, the master builder of the RI Philharmonic Orchestra, could be heard playing the occasional piano recital at the Ocean View retirement community in Falmouth, Maine where he currently resides, bringing joy to his friends and neighbors. And while he has not been an active part of the RI music scene for over 30 years Madeira’s legacy still actively plays in the hearts and minds of music lovers in the Ocean State. Due to his foresight, craftsmanship and perseverance the RIPO organization has grown and prospered in all its component parts – the regular subscription series, the Rush Hour family concerts, the RI Youth Philharmonic Orchestra, the Pops Orchestra, and since the mid 1990s, a music school. Taking over the administration of the former Music School, Inc., a private tax-exempt organization with three outreach facilities in Rhode Island, the Philharmonic has become one of the few symphony orchestras in the United States with its own community music school, instructing young people in various styles of music including the classical music that Francis King Carey Madeira spent his whole professional and academic life sharing with the people of Rhode Island and others in places far and wide.

Francis Madeira passed away on August 28, 2017.

The RI Philharmonic & Music School headquarters at the former Meeting Street School, 667 Waterman Avenue, East Providence

MUSIC DIRECTORS of the RHODE ISLAND PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

FRANCIS MADEIRA 1945-1978

ALVARO CASSUTO 1979-1985

ANDREW MASSEY 1986-1991

ZOUHUANG CHEN 1992-1996

LARRY RACHLEFF 1996 – PRESENT

RIPO ASSITANT CONDUCTORS

UNDER FRANCIS MADEIRA (1945-1979)

Erich Kunzel (1935-2009), Assistant Conductor under Francis Madeira from 1962 – 1965, was later the famed conductor of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra. He was perhaps the most prolific of all the conductors associated with RIPO due to his many recordings on the Telarc label.

Martin Fischer 1949-1961

(Brown faculty, RIPO principl violist, later conductor of the RI Youth Philharmonic Orchestra)

Michael Charry 1961 (April)

(Principal oboist RIPO)

Bernard Rubenstein 1961 (November)

(Principal oboist RIPO)

Erich Kunzel (1962 – February 1965)

(Brown faculty)

Jerome Cohen 1965 (February-April)

(Plymouth Philharmonic music director)

William Stein 1965-1966

(New England Conservatory PhD conducting student)

Jeff Cook 1966-1968, and 1970-1971

(Simmons College faculty)

Charles Fidlar 1968-1970

(Brown faculty)

George Kent 1971-1979

(Rhode Island College and University of Rhode Island faculty, Chorus of Westerly music director, named RIPO Resident Conductor in 1978)

POSTSCRIPT

It has come to my attention that Francis Madeira, founder of the RI Philharmonic died on August 28, 2017. He had been living in Maine for the past 30 years and had turned 100 years old earlier this year.

Coincidentally I finally finished this extended biographic article about him for the RI Music Hall of Fame website. We had communicated back and forth in a series of hand written letters (you remember those, right?) while I was putting the article together over the course of couple of years after his 2014 induction to the RIMHOF. He was every bit as exacting with my writing as I’m sure he was with his music.

I had the pleasure of seeing him conduct the RI Phil while I was a student at RI College at the end of the 1970s, I also had the honor of addressing the audience at a RI Phil concert with Maestro Madeira on stage for the brief ceremony honoring his induction (an illustration of which you can see above).

For over thirty years he was one of the cultural pillars of the RI arts community, and for the RI Philharmonic, since Maestro Madeira passed the baton onto others, the race is still being run – soon with a new Music Director because Larry Rachleff resigned this past Spring. Auditions for his replacement will commence this season.

Gerard H. Heroux, September 10, 2017

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ARCHIVES AND INTERVIEWS

George Kent interview March 2015

William Stein, Facebook messages Spring 2015

Jean and Francis Madeira Papers, RI Historical Society , MS 122

Rhode Island Philharmonic archive of concert programs, accessed April 20, 2014

Francis Madeira written notes and corrections Summer 2015

PRINT REFERENCES

Cherkaoui, Tsukasa. “Rhode Island’s WPA Music Project and It’s Orchestra,” from Rhode Island’s Music Heritage: An Exploration, edited by Carolyn Livingston and Dawn Elizabeth Smith. Sterling Heights : Harmonie Park Press, 2008.

Lee, Leslie Ricci. “The Rhode Island Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, 1954-2007,” from Rhode Island’s Music Heritage: An Exploration, edited by Carolyn Livingston and Dawn Elizabeth Smith. Sterling Heights : Harmonie Park Press, 2008.

Olmstead, Andrea. Juilliard : a history. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Rodi, D. Richard. A History of the Rhode Island Philharmonic. (Place and publisher not listed), 2005.

WEB REFERENCES

Affelder, Paul. “Four Sonatas Offered at Third Annual Olga Samaroff Memorial Concert,” Brooklyn [NY] Eagle, Friday, May 9, 1952, Pg.11 “Music” column. Portable document file accessed at:

fultonhistory.com/Newspaper

[Madeira performed as a collaborative pianist with cellist Elsa Hilger in Claude Debussy’s Sonata for Cello and Piano at Town Hall, Manhattan, as part of a 1952 recital in honor of his former piano teacher, Olga Samaroff.]

Brann, Marc. “Falmouth House Activities,” Ocean Views Newsletter, Winter 2012-2013

http://www.oceanviewrc.com/category/newsletter/

[Francis Madeira’s most recent piano recital – paragraph.]

Cook, Jeff Holland. “Jeff Holland Cook – Resume,” webpage, accessed Dec. 30, 2015.

http://jeffhollandcook.com/resume.html

Cugell, Morgan C. “Brothers, Sing On! Music at Old Avon Farms,” Notable Alumnus: sidebar: Francis K. Madeira ‘34, The Avonian Fall 2010, p. 21.

http://issuu.com/avonoldfarms/docs/avonian_fall2010_m

“Distinguished Alumnus Awards, Award Recipients ’10,” Avon Old Farms School webpage accessed Jan. 13, 2015.

http://www.avonoldfarms.com/page.cfm?p=1761=

“Eleanor White” obituary, May 1, 2003, Yellow Springs [OH] News webpage.

http://www.ysnews.com/old/stories/2003/may/050103_obits.html

[Reports on the April 23, 2003 death of Madeira’s sister, Eleanor.]

“Erich Kunzel,” Wikipedia webpage accessed October 26, 2014.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Kunzel Eriksson, Erik.

“Jean Madeira,” All Music webpage, accessed Jan. 1, 2015.

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/jean-madeira-mn0002183789/biography

“Francis Madeira” inductee details, Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame webpage, accessed Jan. 31, 2015.

http://www.riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?crit=det&iid=282

[Inaccurate dates for the founding concert and first season tour.]

“Francis King Madeira,” Who’s Who website article purchased March 15, 2014.

https://cgi.marquiswhoswho.com

Gray, Channing. “R.I. Philharmonic founder Francis Madeira to be inducted into R.I. Music Hall of Fame,” Providence Journal website article published May 8, 2014.

http://www.providencejournal.com/features Gray, Channing

“RI Philharmonic, kicking off 69th season, finds success with music director Larry Rachleff,” Providence Journal website article published September 19, 2013.

http://www.providencejournal.com/features/

J.C.D. “Jean, Francis Madeira Receive Warm Welcome,” The Wilmington [NC] News, May 3, 1957, p. 7, Google webpage accessed via:

http://news.google.com/newspapers

[Review of a 1957 vocal recital in Wilmington, NC given by Jean Madeira accompanied by her husband who also played a few solo piano pieces]

“Jean and Francis Madeira Award,” Brown Club of Rhode Island web page accessed October 26, 2014.

http://alumni.brown.edu/clubs/BrownClubofRhodeIsland/Madeira.html

Langer, Emily. “Erich Kunzel, 74, Dies; ‘Prince of Pops’ Directed Cincinnati Pops to Fame,” Washington Post, website article published September 2, 2009.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn

Longstreth, Peg Goldberg. “Remembering Erich Kunzel, the ‘Prince of Pops’,” Fort Meyers Florida Weekly website article published September 9, 2009.

http://fortmyers.floridaweekly.com/news/2009-09-09/Arts_Ent/080.html

Madeira, Francis. “Fight to improve treatment of mentally ill continues,” letter to the editor, Portland [ME] Press Herald, July 9, 2013.

http://www.pressherald.com/2013/07/09

[In which Madeira mentions his mother’s work for the National Mental Health Foundation.]

“Martin J. Fischer” obituary, January 8, 2012, Obits for Life webpage.

http://www.obitsforlife.com/obituary/445496/Fischer-Martin.php

[Reports on the Dec. 24, 2011 death of Martin Fischer, the first assistant conductor of the RI Philharmonic.]

“Memorial: Percy C. Madeira ’36, ” Princeton Alumni Weekly. June 11, 2008, webpage accessed via:

https://paw.princeton.edu/issues/2008/06/11

[Reports on the Jan. 16, 2007 death of Percy C. Madeira III, Francis Madeira’s older brother.]

“Mission/History/Vision,” Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra & Music School webpage accessed December 31, 2014.

http://riphil.org/Orchestra/Overview/MissionVisionHistory/tabid/166/Default.aspx

Mitchell, Martha. “Encyclopedia Brunoniana: Music,” Brown University webpage accessed Jan16, 2015.

http://www.brown.edu/Administration/News_Bureau

“Our Clients,” Sound Dynamics Associates webpage accessed February 12, 2015

http://www.sd-associates.com/Clients.htm

[This company has been recording and archiving RIPO concerts since 1975, possibly the only source for audio of Madeira conducting his orchestra.]

“Our Director: Charles Fidlar,” Torrington [CT] Symphony Orchestra webpage accessed January 1, 2015.

http://torringtonsymphony.org/page4.html

“Palace Theatre (Ocean State Theatre, Performing Arts Center) 220 Weybosset Street, Providence, RI,” Jerry’s Brokendown Palaces weblog accessed Jan. 16, 2015.

http://www.jerrygarciasbrokendownpalaces.blogspot.com

“Percy C. Madeira ’36,” June 11, 2008: Memorials, Princeton Alumni Weekly archive webpage.

http://www.princeton.edu/paw/archive_new/PAW07-08/14-0611/memorials.html

[Refers to Madeira’s brother Percy C. Madeira, III (1916-2007).]

“Percy C. Madeira, Jr. Papers 1863-1962 (bulk 1916-1933)” online collection guide University of Pennsylvania, University Archives and Records Center webpage accessed Jan. 31, 2015.”

http://www.archives.upenn.edu/faids/upt/upt50/madeira_pc.html#ref16

[Includes biographical information about Madeira’s father, Percy C. Madeira, Jr.]

“Raymond Jackson, Concert Pianist: Biography,” webpage accessed January 27, 2015.

http://www.raymondtjackson.com/biography.htm

“Rhode Island Philharmonic, Francis Madeira, Music Director” advertisement, The Cowl, vol. XXXIII no.4, Oct. 23, 1970, p.7, Providence College webpage accessed via:

http://digitalcommons.providence.edu/cowl/index.8.html

“Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra,” Wikipedia webpage accessed October 26, 2014.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhode_Island_Philharmonic_Orchestra Summers, Jonathan.

“Olga Samaroff,” Naxos webpage accessed January 18, 2015.

http://www.naxos.com/person/Olga_Samaroff_1209/1209.htm

[Brief biography of Madeira’s piano teacher at Juilliard, includes a discography.]

“Violinist Barbara Bartow Ran Music Box,” obituary, May 12, 2011, Vineyard Gazette webpage.

http://vineyardgazette.com/obituaries/2011/05/13/

“Wriston, Henry Merritt (1889-1978),” Brown University Office of the Curator, Portrait Collection website accessed Dec. 31, 2015.

http://library.brown.edu/cds/portraits/display.php?idno=178