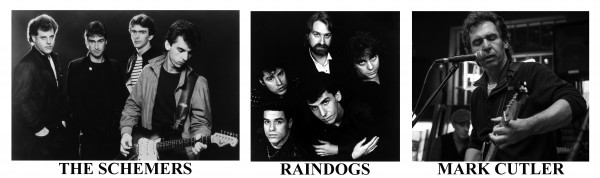

The Schemers/Raindogs/Mark Cutler

by Rick Bellaire

The formation of The Schemers in 1978 mirrors the history of hundreds of other bands on both sides of the Atlantic whose eyes were opened to the possiblity of pursuing a career playing original music when the music press began to present regular coverage on the Punk/New Wave scenes which had sprung up in London, New York City and Los Angeles in the late 1970s.

A “do-it-yourself” ethic had evolved amongst the acts which encouraged the artists to focus almost exclusively on their music and not on the “brass ring” of rock stardom. It was art for art’s sake, with the bands seeking only the approval of their peers and the core audiences on the scenes they’d created for themselves. This approach turned the tables on the record companies and turned into a new way of doing business, at least for a few years. The bands didn’t have to go looking for a record deal – the labels came looking to sign them.

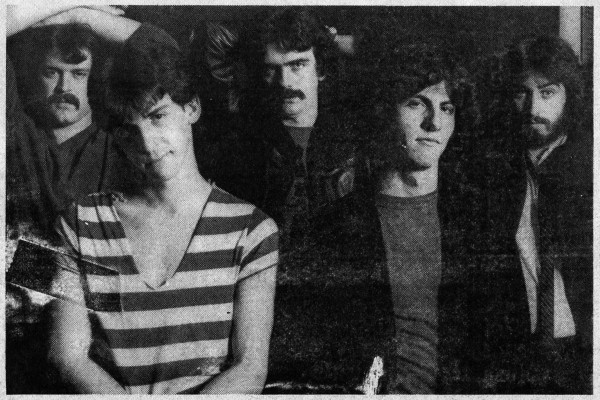

Mark Cutler first stepped onto the path from which he would never stray in the mid-1970s when he placed an ad in the Rhode Island alternative weekly The NewPaper offering his services as a singer and guitarist. He received a call from a Brown University-based band called Windy Mountain. Mark joined a lineup consisting of vocalist Eleni Kelakos, pianist Mark Grimm, guitarist Dave Grice, bassist Pete Allberry and drummer Rick Webb. The group found success on what was then still considered an “underground” scene which revolved around two of Rhode Island’s most popular bands, Rizzz and Wild Turkey. Like those bands which performed both covers and original material, Windy Mountain shied away from the Top 40 and focused on favorite FM radio album tracks by a wide range of artists from Little Feat to Pure Prairie League to The Allman Brothers Band and everything in between and began adding songs written by Grice, Grimm and Cutler to their repertoire.

Mark Cutler quickly developed into the band’s most prolific songwriter and he, Webb, Grimm and Allberry broke off from Windy Mountain to form a band called The Users to concentrate on his material. The band’s Brown University connections helped to move them onto the campus-related music scene and brought them to the attention of Bernard “Uncle Bernie” Larrivee, Jr., a DJ on Brown’s FM radio station WBRU, who began to play their demos on his show. Things were looking up, but there was still a missing ingredient in Mark’s eyes: a second guitarist. Since childhood, Mark had been enamored by the two-guitar interplay between Brian Jones and Keith Richards which had been the backbone of the early Rolling Stones sound and had recently become of aware of a similar approach being utilized by Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd of the up-and-coming New York band Television. He was eager to explore the possibilities of – as Keith Richards dubbed it – “the ancient art of weaving.”

Guitarist Emerson Torry began his professional career in the early ‘70s playing in Raven, a hard rock cover band which also featured future Steve Smith & The Nakeds drummer Joe Groves. By the mid-1970s, he had graduated to an original band called Fingers. The other four members of the group were bassist Dave Slamowitz, drummer Rodney Maturi, lead guitarist Bryant Montiro, and singer-songwriter Ed Tabela. With this band, Emerson began to formulate two concepts which have informed his musical approach throughout his career. The first is that two guitarists playing together need not be limited to the common “lead” and “rhythm” roles so prevalent in Rock ’n’ Roll. Although leaving the bulk of the soloing to the virtuosic Montiro, Emerson was also a big fan of the guitar styles of the early Stones and Television and began pushing the limits of his rhythm guitar slot into that of a “second” guitar by developing intertwining arpeggios, hook-like riffs and harmony lines. The second lesson so well-learned during this time was that it’s all about the song. The band’s hard-rocking arrangements were designed to provide the best possible backing for Tabela’s compositions and voice.

Fingers at Koerner’s: Emerson Torrey’s first original band seen here in the mid-1970s with the staff of Koerner’s Lunch: Bryant Montiro, Emerson Torrey & Ed Tabela (back row), Dave Slamowitz & Rodney Maturi (seated). The historic diner was located on Aborn Street in downtown Providence directly behind the original Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel and kitty-corner across Westminster Street from the original Living Room. Thanks to the cheap eats and diesel-strength coffee, the lunch room became a favorite gathering place for musicians in the early days of the two important original music venues.

The setting for the birth of The Schemers was the evolution of The Living Room (a small music venue in downtown Providence) from a jazz, blues and folk club into a platform for bands playing original music. The club was opened in 1975 by Randy Hein, an entrepreneur whose previous experience had been as the operations manager of the Palace Theatre, a successful mid-level rock concert hall two blocks from The Living Room.

By 1977, the club was struggling. Randy and his partners, his brother Brian and their friend Carl Sugarman, knew that change was in the air. They had been keenly following the development of the scene based around CBGB in Manhattan and decided to have a go at presenting local original music. CBGB had undergone a similar evolution (the initials stood for Country, Bluegrass and Blues) and had slowly morphed into the epicenter of the American Punk/New Wave movement, homebase for some of the most important and successful bands of the era including The Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, The Patti Smith Group and the aforementioned Television. The Living Room quickly became the focus of the new Rhode Island original music scene and provided the meeting place for like-minded musicians including the members of The Users and Fingers.

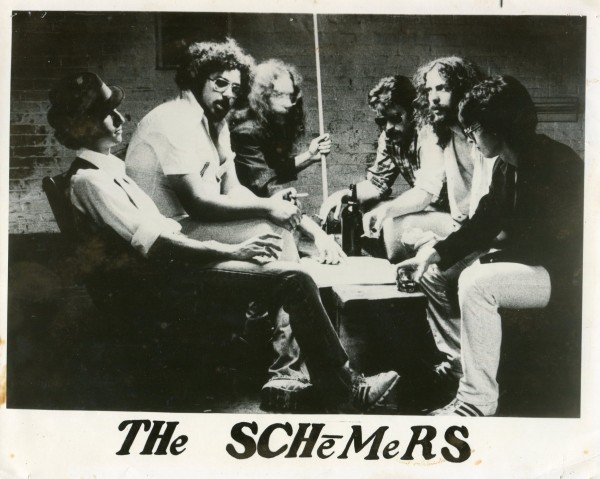

The original lineup of The Schemers came about when Rick Webb introduced Cutler, Grimm and Allberry to Torrey and Tabela. The new group set about working on original material from Tabela and Cutler. As lead singer, Ed sang both his and Mark’s songs, but, in short order, stylistic differences arose as it became clear that Cutler’s songs defined the direction in which the band was heading. Tabela left the group in 1979 on good terms and reunited with Bryant Montiro to work on Ed’s material. Mark moved out front into the position he would hold for the next eight years: lead singer, lead guitarist and songwriter for The Schemers.

(This close-knit gang of musicians continued to support each other and interact musically for years with members of the first three lineups of The Schemers providing backing for Tabela’s solo records and Ed and Bryant often filling the opening slot at Schemers shows. Ed Tabela passed away in 2012.)

Rick Webb also left the band around this time and was replaced on the drums by Rene Blais, an energetic, hard-hitting player. One more piece of the puzzle was now in place.

Although the band’s popularity was growing by leaps and bounds, playing original music was still a hard row to hoe, especially financially speaking, and in 1980, Allberry and Grimm threw in the towel. It was decided that the group would not look for a new keyboard player and would continue on as a four piece focusing on the unique guitar sound and close harmony singing which had developed so naturally and quickly between Cutler and Torrey. Mark brought in his friend Jimi Berger on bass guitar.

Jim was a classically-trained clarinetist who grew up performing with youth orchestras. In high school, he also began dabbling in popular music in an acoustic duo with Margie Weinstein. (As Margie Wilde, she would later go on to local fame as lead singer of Hi-Beams, a band which will play an important role in this story a few years down the road.) Jim was a solid rhythm section player with a melodic flair reminiscent of Paul McCartney and Brian Wilson and also brought a third voice to the table. He was an intuitive harmony singer and could add a third part to the vocal mix and opened the door to having two-part backing vocals provided by him and Emerson behind Mark’s leads.

With the recruitment of Jim Berger, the final piece of the puzzle was in place and that – as you will read when you continue on to the next section – is where our story really begins…

FAREWELL TO THE SCHEMERS

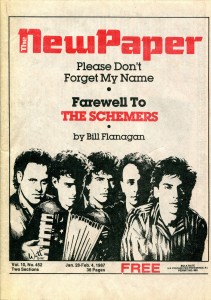

by Bill Flanagan

The following article originally appeared as the entire arts section of the January 28, 1987 edition of The NewPaper, a weekly alternative newspaper published in Providence, Rhode Island from 1978 to 1993. It is reprinted here by kind permission of the author.

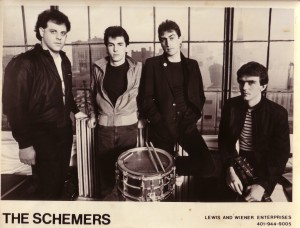

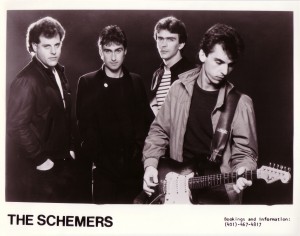

The Schemers will play their final shows, at Lupo’s, this Friday and Saturday, about seven years after they began their slow climb to become the top band in the state. Singer/songwriter/guitarist Mark Cutler is starting a new band in Boston with the rhythm section from Red Rockers. Cutler announced his decision – breaking up the band – almost three months ago. Since then The Schemers have been working to pay off some band debts. Guitarist Emerson Torrey will join Tom Keegan & The Language, keyboardist Dick Reed and drummer Matt Koomey will move to Manhattan, and bassist Jimi Berger is going to spend some time with his family before deciding his next move.

The Schemers have been called the best Rock ’n’ Roll band Rhode Island ever produced, and though there have been two or three other groups which could give them a run for that honor, no one would feel comfortable making the claim for another band as long as The Schemers existed. Keith Richards once said that the greatest Rock ’n’ Roll band in the world is a different band every night. There have been nights when The Schemers seem to be the very best.

The now iconic Schemers logo was created by their friend Gertrude Chung when the band asked her to write out “Rock & Roll Music” in Japanese. Finding no verb equivalents, she wrote it out as out “Sway Flow Music” and thoughtfully provided the western world with the English translation.

And maybe that’s why they have to break up. The Schemers have managed to grow and improve for seven years. If they stayed in Providence any longer, they’d get stale; they’d start repeating themselves. They’d turn into the Rhode Island version of Southside Johnny & The Jukes. So, let them go out on top. and before anyone says that it’s a shame that they never made it big, never made a record for a major label, let’s remember how many great songs they wrote and how many great performances they gave. The Schemers reached more people, moved and inspired and made sense for more people, than a lot of big stars ever will. Because of the audience, The Schemers really mattered. They articulated exactly what it felt like to be living hungry in New England in the 1980s. And it as not affected, it was real. The Schemers were their audience – they weren’t separated by backstage passes or videos or record labels. The Schemers’ audience knew the girl in the “red Thunderbird” and the suicide in “Walter Jumped.” The Rhode Island audience knew Cutler and the people in his songs. They were the people in his songs.

That’s an intimacy big rock stars on major labels can approximate but never really achieve, and very few local bands have the talent or courage to summon. But how long could a small Rhode Island audience keep asking Mark Cutler to open his veins in public? How long can you turn local life into Rock ’n’ Roll before the vitality is replaced by affectation or voyeurism? The Schemers did it right, they did it real and they did it long enough. Which doesn’t mean they won’t be missed, they’ll be missed like crazy.

The Schemers gestated in the late ’70s as a vaguely focused bar band with Ed Tabela on lead vocals and Cutler and Torrey on guitars. But the group began its real life in the spring of 1980, when Cutler took over the singing and Rene Blais came in on drums. Cutler’s voice was rough then; he had a hard time singing a whole night and always had a sore throat. He wore glasses on stage and while obviously a hot guitarist, he sometimes overplayed and got sloppy: the Alvin Lee factor.

But even then, the songs stood out. Cutler wrote like an excited kid, about cars and girls and pent-up energy. “High Fashion Girl,” “Red Thunderbird” and “Poor Little Johnny” are the best-known songs from The Schemers first era. Cutler sang about teenagers who killed themselves by jumping off the Newport Bridge and mothers who killed themselves by smoking cigarettes. He sang about how meeting the right girl was like summer vacation. It was kid stuff, but great kid stuff – ‘cause it was written and sung by a real kid.

In the summer of that year, The Schemers lost their keyboard player (Mark Grimm) and bassist (Pete Allberry) to marriage. They decided to go on as a quartet; Cutler brought in his childhood friend (and Schemer roadie) Jimi Berger on bass and forgot about keyboards. Thus was born the four-man band that lasted three years and contained most of The Schemers evolution.

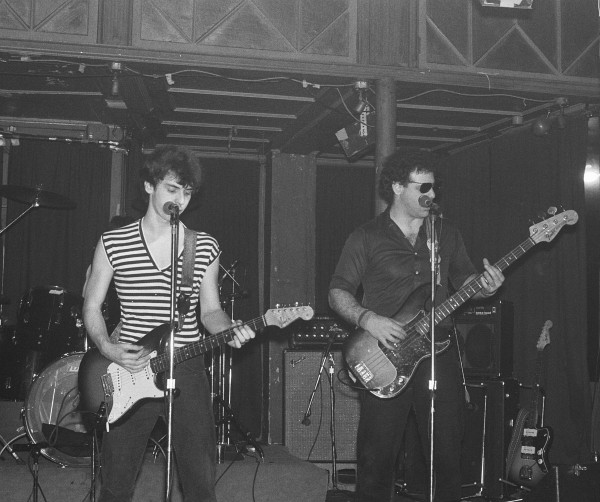

Cutler/Torrey/Berger/Blais started out a little shaky, but very quickly found their focus as a guitar band. Cutler’s playing calmed down, became more controlled and melodic. He and Torrey absorbed the tricks of great guitar teams from the Stones to Television, developing unusual textures and a wide web of sounds. In 1981, The Schemers began playing every Wednesday at the old Living Room on Westminster Street. Over that year the guitar interplay between Cutler and Torrey became magical. Like the Stones, the rhythm was all coming from the guitars; Blais and Berger were following Cutler and Torrey. Songs like “Laughing Up My Sleeve,” inspired by a John Coltrane riff, could break your heart with sound alone. The words didn’t matter.

During that time, it became obvious why Mark Cutler was so dedicated to this particular group: Torrey, Berger and Blais were absolutely resolute in their belief in, and loyalty to, Cutler. What Mark said went. If Mark said, “Play this,” they played it. Emerson and Jimi (who were both a few years older) became protective big brothers to Cutler, the hyper-talented kid. The band developed into a tight family, even moving in Berger’s house in Cranston. People could hang out with The Schemers, have laughs and arguments and parties with The Schemers – but there was a part of The Schemers that was closed to outsiders. Some locals saw this as arrogance (how often did some frustrated, would-be groupie moan, “Them Schemers are stuck-up snobs!”), but it was completely necessary as a vehicle for their work and as a barrier against the worst elements of the Rock scene.

Other local bands swap musicians like poker chips, ditching one player as soon as a better technician shows his face. But The Schemers were brothers, living together, covering for each other and growing together. The only Rhode Island band with a comparable shared faith and loyalty has been Beaver Brown.

Before long, The Schemers were making noise beyond The Living Room’s tiny New Wave clique. Tony Lioce championed them in The Providence Journal and The NewPaper took them to its bosom. They won the WBRU Rock Hunt in 1982 and put out their first record, “High Fashion Girl.”

The EP featuring the winners of the 1982 Rock Hunt featured the band’s first released recording, “High Fashion Girl.”

That was a mistake. The song was one of The Schemers’ oldest and their first crowd-pleaser. So even though the band had by that point outgrown its teenage sentiments, they chose it as their vinyl debut. Cutler had seen the song’s use of Neil Young’s “Cinnamon Girl” chorus as an obvious reference, a homage. But other people, including Bob Angell writing in The NewPaper, thought it was a ripoff. The criticism of “High Fashion Girl” stung and it probably spurred The Schemers next step, a move in Cutler’s writing away from adolescent subjects, away from “girls” to songs about darker emotions and a more grown-up world.

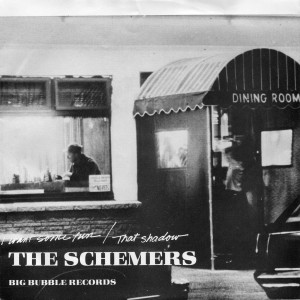

“I Want Some Fun For Once In My Life” was the next signature and it marked The Schemers’ growth. Cutler’s visions were still romantic, but they weren’t rosy. In “Danger Avenue,” “That Shadow,” “Who’s Right” and a dozen other songs, he measured out the pain that comes with attachments, the pound of flesh that’s cut out when you open yourself up and the jealousy that’s the flip side of love. Those were songs about everyone wanting a piece of you and (this is what made The Schemers special) admissions about wanting a piece of someone else. The Schemers’ music turned hard and relentless, and in performance Cutler often projected rage. His vocals grew stronger all the time. More than a solid base, the rhythm section became a hammer. Some nights it was almost too hard, too real, to be fun. There was nothing safe or pretty about Cutler wailing, “I Got Control!” while Blais and Berger pounded out a beat like a migraine. There was, though, a determined willfulness (much like that of “Gimme Shelter”) in the whiplash insistence of “We’re gonna set this straight before the daylight comes…we’re gonna see who’s right by the end of the night!”

It was great. And the fact that The Schemers had outgrown their early style was evidence of a potential for change that would keep them vital. But finally it was like painting with one color all the time. The Schemers had developed into the fastest car on the track, but a car that could only move in fifth gear. Maybe Cutler was playing havoc with his personal life to keep the music coming. Some songwriters do that. He needed to grow again, to try something other than banging his head on a wall. The rhythm sections was too rigid, too unswerving in its 4/4. There was a rough emotional band meeting at the Cranston house at which Cutler – never comfortable with confrontation – announced that if the rhythm section didn’t work on its chops he would leave the group. It is a measure of The Schemers’ closeness that instead of bitching or making excuses, Blais and Berger buckled down and worked at their instruments. They turned a tense situation into inspiration to improve greatly. By this time, too, The Schemers cut themselves loose from local management which had them signed to a contract which one objective expert termed “slavery.” The bugs were ironed out. They were ready to do their best work.

In 1983, The Schemers achieved prominence in Rhode Island. In the early part of the year they cut their single “Some Fun” at Blue Jay Studio in Massachusetts, with sidemen Dick Reed on organ and Klem Klimek on sax. The Schemers played dates in Boston and New York, and the new Living Room gave them a home base. One night, John Cafferty came in and was knocked out. “I always heard about this band,” he said, “but I couldn’t believe it when I saw them. They had everything just right.” Cutler and Cafferty began a friendship and as Beaver Brown became famous in the rest of the country, The Schemers sometimes opened their shows.

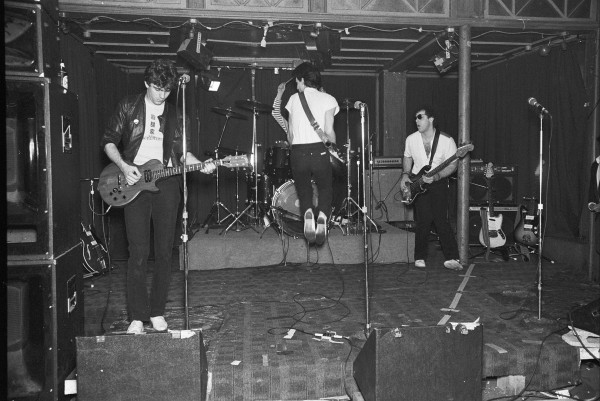

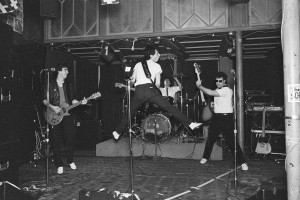

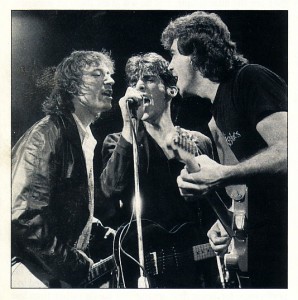

Now THAT’S Rock ‘n’ Roll! Candid performance shots of The early Schemers on stage at their home base, the original Living Room on Westminster Street in Providence, Rhode Island.

The NewPaper’s Scott Duhamel said at the time that the biggest difference in The Schemers was the confidence they showed when they stepped on a stage: “There’s no longer any fear in their eyes when they see a new audience.” The clearest example of this was the band’s willingness to cut the volume for slow, quiet numbers like “Gentleman Jim,” a country waltz so simple and open that most rock singers would be scared to death to stand up and sing it straight. In country-tinged songs like “I Could Get Used To This” and “Valley Of Love,” Cutler wrote with remarkable poetry and candor about the life he and his audience were living:

I’d like to wake up from this bad dream

It’s so dark in here, I can’t see too clear

Come in the night, let me see your face

Let me hear your voice in a quiet place

If it’s right, I’m gonna hold on tight

It was the perfect Providence song, but it also showed the first trace of isolation in the singer. Cutler was beginning to stand a little apart from his audience, from his friends, in his songs. That tendency would develop over the next three years.

“Stars” had always occupied Cutler’s songs, but for the first time the singer seemed to think stardom might not be all it’s cracked up to be. Many young musicians start out playing at being rock stars, going through the local gigs halfway between pretending they’re at Madison Square Garden and imagining that they’re “paying their dues” so they’ll have something to talk about in interviews once they get big. In other words, they are living in the future. But at some point, after doing it for a few years, it dawns on a musician that there might not be any big payoff – that where he is may be as far as he ever gets. That that audience he plays to that night may be the most important crowd he ever has. It’s a big realization, and a great many players quit right then. It sinks in that it’s not a game and so they pick up their balls and go home. Some musicians, though, when the realization hits, just get strong and get down to business. Sometime around the winter of ’83/’84, The Schemers got strong, and they started living in the present. In “Satisfied” – one of the least satisfied songs ever written – Cutler screamed out a premonition felt by every aging rocker trying his best to make it through one more New England winter by dreaming of the beach days ahead: “Lately I have this fear/What if summertime ain’t easier?”

1984 saw The Schemers entering their responsible period. Where they once sang of the excitement of streamlined hearts and Danger Avenue, they were now fixing each illicit pleasure with a mighty burden of guilt and penance. Cutler wrote of searching for a “better way,” he asked a woman to “make me understand” how to behave better. He even came up with a tune that listed all the failures his woman accused him of and finished each verse, “you’re right again.” Cutler wrote about being torn between wanting to die young and hip, and feeling obligated to live long enough to create something that would last:

I got me a friend and he’s living inside his cave

He don’t have the best luck so he plays all day and night and day

I know that I should help him, but then I give in

My woman’s back home, she thinks I’m doing other sins

I can’t go, not just yet

The refrain was, “Still I get no peace.” The band that once demanded “some fun” now aspired to “More Than A Real Good Time.”

These were unusually sober sentiments, but The Schemers’ popularity kept expanding. They entered the WBCN Rumble – the most important battle of the bands in the Northeast – and were selected as quarter-finalists. It was around this time – the spring of ’84 – that Rene Blais announced he was quitting. Getting married meant taking adult responsibilities – and regardless of how bright The Schemers’ future looked, Rene just didn’t want to be hungry anymore. It was the first crack in The Schemers’ brotherhood and over-zealous fans treated Rene as if he were a home wrecker. One night at The Living Room, a Schemer loyalist lectured Rene that the spirit of Rock ’n’ Roll was to be hungry, to sacrifice, to live on the street for the sake of the music. This caused the drummer to blow up. “What are we?” he demanded. “Serfs? Peasants put here to suffer and dance around for the amusement of the nobles? Am I supposed to go hungry so that I can get up on a stage and live out the Rock ’n’ Roll fantasies of the critics and The Living Room?”

Rene was replaced by The Hi-Beams’ Matt Koomey, a versatile drummer with the time-keeping equivalent of perfect pitch. Matt had so sure a sense of where each beat fell, that he naturally played around the beats – hitting a little before or a little after – adding simple but propulsive accents without crowding the rhythm. Loosened up by Koomey’s approach, bassist Berger played with a new fluidity; The Schemers’ rhythm section cracked with confidence. The band decided to break Matt in at the WBCN Rumble, a risky move. They also brought in – temporarily – old standby Klem to bolster the new lineup with sax. Going into the Rumble with new players was taking a big chance, but it paid off. They beat all the odds and took the whole contest in June of ’84, picking up a video, a appearance on MTV and a great deal of Boston press. In the fall of ’84, they added the other alternate Schemer, keyboardist Dick Reed, as a full-time member. It said something about Cutler’s evolution as a band leader that he now felt comfortable having working pros like Koomey and Reed in his group. Once The Schemers’ family loyalty had been the most important factor. Now the band was self-confident enough to include the contributions of musicians who did not necessarily share Emerson’s and Jimi’s big brother devotion to Mark.

So, the final lineup – Cutler/Torrey/Berger/Koomey/Reed – was fixed. In the next two and a half years, The Schemers would consistently get better, and consistently get nowhere. As a Rock ’n’ Roll band, they were superb. Once Cutler had been shaken by accusations that “High Fashion Girl” was too close to Neil Young. Now he stood toe-to-toe with his influences. Was “Satisfied” based on the same groove as Dylan’s “From A Buick 6?” OK, The Schemers would play both songs. Did he want to take a piece of the chestnut “Cottonfields?” He was right up front about it, mixing guilt with bravado and singing of an apocalyptic day when all sorts of hell would break loose and “I Won’t Hurt You Anymore.” It was both a prayer for a man to be able to control his violent side and an admission that the day he stopped hurting people would be the day hell froze over.

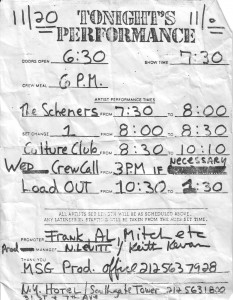

The Killer meets The Schemers: The band is seen here with the legendary Jerry Lee Lewis in the basement dressing room of Lupo’s when they opened for him in the mid 1980s.

The Schemers played New York more and more often, though Boston never truly took them to its bosom. (There seemed to be a few quarts of sour grapes over the upstart Rumble win.) A showcase performance at The Bottom Line in N.Y.C. led to a two-night stand with Culture Club at The Centrum in Worcester. In Rhode Island, The Schemers succeeded Beaver Brown as the kings of the ant heap, as popular with blue-collar cover fans as with the Living Room hipsters. Record companies were always interested, always poking around, but never made concrete offers. (Publishing deals were shoved away; Cutler wanted to control his own songs, though he gave the other Schemers pieces of them.) In mid-1985, The Schemers signed a one-year production/management deal with a powerful record biz attorney in Philadelphia. At least one major record label sent word through channels that they would love to sign The Schemers – as soon as the band got rid of the big lawyer. Here was a real problem for a bunch of Providence boys. Should they listen to the lawyer who said he could keep the labels from screwing them – or to the labels, who said the same about the lawyer? The band was divided. Kooky believed in the lawyer. Reed believed in the labels. Cutler desperately wanted to believe The Schemers were not going to have to go back to square one.

The Schemers always had bad luck with managers. They had been handled by friends (not such a good idea when it was time to do business) and by shady business types who took their money and promised them the world. The last lawyer – the big time show biz cat – was their big hope, and the five Schemers would probably give five different accounts of his character. Some would declare him a great opportunity missed and others would say he was a land mine avoided. No one will ever know for sure, period. By the time their one-year contract with the big shot came up for renewal, in the summer of ’86, Cutler was already being romanced by the former Red Rockers. The other Schemers didn’t know that. Cutler still hoped things would work out with The Schemers, that the lawyer would be able to close a record deal, as he said he was close to doing. Cutler and Reed went to New York for a meeting with the manager of one of the top British rock groups. This manager (who was not looking for new acts himself) had offered to advise them on whether to re-sign with the big shot lawyer. The manager read all the agreements and told The Schemers that they should under no circumstance renew the lawyer’s contract. They should go back to Rhode Island and start again.

In retrospect, it seems likely that this was one disappointment too many for Cutler. Yes, the major labels were still talking, and sure, the loss of the lawyer might even remove an impediment. OK, John Cafferty was plugging for them and T-Bone Burnett said he wanted to produce them, and Warner Brothers Records’ George Skaubitis was working so hard that you’d swear he was born in Cranston. But how many times can you be told your business is being taken care of only to have the rug pulled out? It all came down to the same question: Where are you going to spend your life – in the future or the present?

Cutler’s theme of being detached from the people around him, there as early as “Valley Of Love,” kept reappearing in his songs. Each time the degree of separation was increased. “I don’t need an answer,” Cutler sang, “I need a time machine.” In 1986, he turned out “Up In The Air,” a ringing, moody march closer in mood to R.E.M. than the familiar Schemers style. Now Cutler’s narrator was literally disembodied – floating above his old home, his old lover, unable to make himself seen or heard. The Schemers last local hit “Remember” – a plea from a would-be artist to not be forgotten, a declaration of Cutler’s intention to leave some mark on his hometown. “Please don’t forget my name,” he sang. “You never really die if your memory is alive.”

Given that they did have a strong local following and promise of record label interest, the other Schemers didn’t take it seriously when Cutler told them about the Red Rockers’ offer. Dick Reed said at the time, “Mark’s not going to give up The Schemers. He’s not crazy.”

But people underestimated how long Cutler had been living on promises of the golden days right around the corner. The same part of Cutler’s personality that has consistently pushed The Schemers to try new things could not be contend to spend another five years as the star of the four Ls – Leo’s, Lupo’s, The Last Call and The Living Room. Some guys are perfectly happy being big fish in small ponds. But sitting around Providence having your back slapped is a trap. Apparently Cutler decided that regardless of whether or not it was a better business move, he would rather try something new than turn into a local cartoon. He told The Schemers he was out.

For the Providence Rock ’n’ Roll community, the end of The Schemers is a big loss, but not unprecedented. About every five years the old cafe society seems to clear out to make room for new kids. It happened in 1974, when The Fabulous Motels disbanded and the whole East Side Charlie Rocket/Talking Heads/Scott Hamilton crowd left for New York. The way for The Schemers’ local ascension was cleared by the 1980 breakup of The Young Adults and the subsequent migration to New York of David Hansen, The Mundanes, The Egyptians and The Debs. No doubt there are other young artistes waiting to win the Rock Hunt and hold court at Leo’s. Good luck to them.

“Poor Little Johnny” was one of the first Schemers songs to win popularity with the local crowd, in 1980. It was also one of the first times that The Schemers hit on the musical mix that would give them much of their best material: a mid-tempo Chuck Berry rhythm with almost-country guitars rocked along under a Dylanesque vocal and Everly Brothers harmonies. As it was a prototype for so many good tunes, “Poor Little Johnny” would be a significant song even if its lyric did not become more poignant as time goes by. But it has.

In the song, Johnny has to flee his hometown because he’s been blamed for a crime. Maybe it’s his own fault (“He let every little thing go to his brain”) and maybe it’s not (“I know when you’re set up it ain’t easy”). What makes the lyric stay in your head isn’t its plot, any more than the plots matter in “Up In The Air” or “Time Machine”: it’s the sense of being forced to leave your home and friends. “Poor Little Johnny” was the last song played at the old Living Room before the wrecking ball descended. That night it was hard not to be struck by the first lines of the last verse:

We all miss you, John, you’re in our thoughts

I hope you’ll remember all the friends you forgot

It was a fitting auld lang syne then. Thinking about what The Schemers have meant to Rhode Island, those words seem even more appropriate now. And the last line says it best:

I want you to know we’re all rooting for you

©1987, Bill Flanagan

THE STORY OF RAINDOGS

by Rick Bellaire

Give my umbrella to the rain dogs

For I am a rain dog, too

– Tom Waits, 1985

The popular notion of a “rain dog” is that of a domesticated canine – someone’s pet – which can’t find its way home.

In the days before leash laws became the way of the world, well-trained, well-behaved dogs were free to roam, to explore the streets of our towns, and they could almost always find their way back before day’s end by following the trail of the scent they’d left behind during their travels. But, sometimes, if heavy rains had washed away those trails, the dogs were left lost and stranded in the city, wanting nothing more than to find their way back home. These were the rain dogs.

Dogs still get lost or are abandoned these days, but those who are lucky enough to evade animal control officers often find each other and revert (by instincts thought to be long-bred out of them) to a pack mentality, banding together to create new “families” for themselves. It’s a representation of “safety in numbers” in its most primal form.

The title track to Tom Waits’ landmark ninth album, Rain Dogs, likens these creatures to the homeless populations in our urban centers who are similarly lost and often band together in search of safety and comfort and a sense of “belonging.”

It’s an apt analogy for the “rain dogs” in this story, all of whom found themselves geographically and musically stranded in southern New England in the late 1980s (and who not-so-coincidentally named their first album Lost Souls).

When they came together in 1987, each of the members of Raindogs had achieved some level of success – some great, some small – during the preceding decade. The common bond which led to their formation was that, for each of the musicians, their individual experiences had proven to be ultimately unrewarding in some way and each of them was searching for something different, something new, something special.

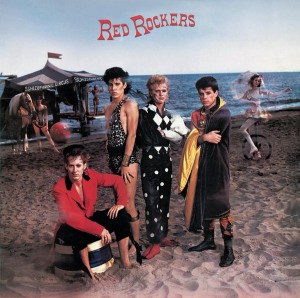

RED ROCKERS RULE!

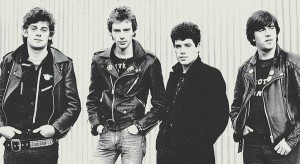

Much like their role models, The Clash, the Red Rockers started their career without a permanent drummer. John Griffith (rhythm guitar and lead vocals), James Singletary (lead guitar) and Darren Hill (bass guitar) grew up in New Orleans where they had been exposed to and influenced by all of the music the melting pot of “The Big Easy” had dished up in the previous 100 years – Cajun, Zydeco, Jazz, and the special brand of funk that is Louisiana R&B. As teens, they gravitated toward the new sounds of punk rock and were inspired to form their first band, The Rat Finks, in 1979 after attending a concert by The Ramones together. The Rat Finks began writing and rehearsing their own material and using pick-up drummers whenever they had the opportunity to perform. They were especially drawn to the socio-political message of The Clash and other left-leaning acts and, once they’d seen The Sex Pistols on their only American tour, they decided to get serious about their future.

The band took on a full-time drummer, Patrick Jones, and changed their name to Red Rockers after the title of one of Darren’s favorite songs, the then yet-to-be-released “Red Rockers Rule” by the California band The Dils (led by future Rank & File cowpunk pioneers Chip and Tony Kinman). The band recorded an EP, Guns Of Revolution, for a local label, Vinyl Solution, which quickly placed them at the forefront of the fledgling New Orleans punk scene. The music press dubbed them “the American Clash” and they remained at the top of the heap for the next two years, opening shows for every major punk and new wave act which came through town including Black Flag, X, and The Cramps. They accepted an offer to tour with The Dead Boys and during the trip, the band came to the realization that they’d have to hit the road if they were going to take things to the next level.

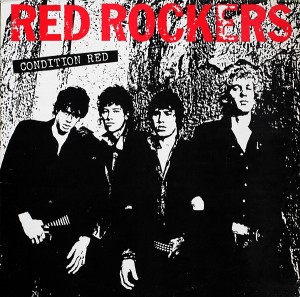

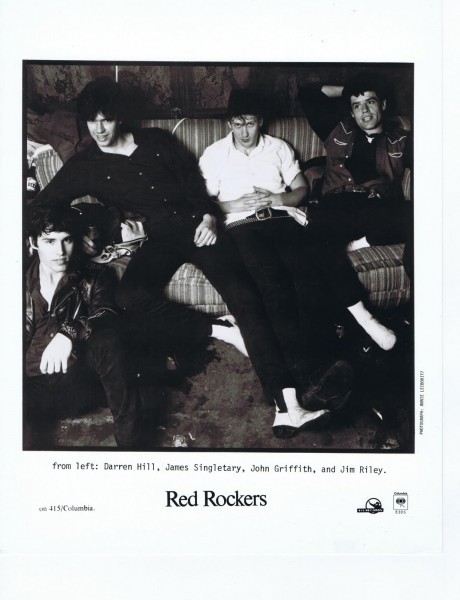

They began writing their first album while working their way out to California where they secured a deal with a new label, Howie Klein’s 415 Records in San Francisco. Working with 415’s in-house producer, David Kahne, in 1981 the band turned out Condition Red, a punk masterpiece with songs by each of the original three members, Darren, James and John, and a cover of Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues” with guest vocalist Jello Biafra of The Dead Kennedys. That track and Darren’s “Guns Of Revolution” started getting heavy airplay on college radio and that, combined with stellar reviews (especially in the punk fanzine community), led to them securing the opening slot on one leg The Clash’s 1982 American tour. They continued to promote the album on tours with their new wave 415 label mates Translator (“Everywhere That I’m Not”) and Romeo Void (“Never Say Never”) as they prepared material for the next album.

STIFF LITTLE FINGER FITS LIKE A GLOVE

When Red Rockers returned to the studio to begin work on their second album, they found themselves at odds with their producer. Kahne began pushing the band to polish up their sound to make it more “radio friendly” with an eye to scoring a hit single. John, who had emerged as the band’s principal songwriter, was willing to give the new approach a shot as were James and Darren, but Patrick decided he’d be having none of it and left the band. His replacement was Jim Reilly.

Jim hailed from Ulster, Northern Ireland, where he got his start playing in hard rock cover bands. When punk exploded in the UK in the late 1970s, he turned his attentions toward the new, raw sound and worked his way up through the ranks to get his first shot at the big time in 1979 when he became the second drummer for Northern Ireland’s biggest punk band, Stiff Little Fingers. He stayed with the group for three albums, Nobody’s Heroes (1979), Go For It (1980) and the live album Hanx! (1980). When SLF disbanded in 1981, Jim wound up in the United States looking for a new musical outlet. By 1983, nothing substantial had materialized and he called an old pal, Paul “Bono” Hewson of the Irish band U2 for advice. Bono suggested he get in touch Howie Klein at 415 Records and the timing could not have been more perfect. Klein introduced him to the Red Rockers and it was a perfect fit.

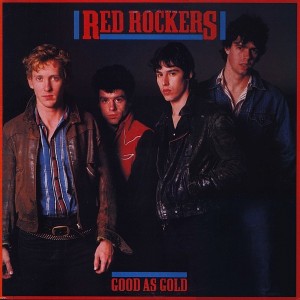

With a new drummer in place, work on the second album resumed with much attention being paid to a song co-written by John, James, Darren and their producer, David. “China” was unlike anything the band had attempted before – a poetic lyric with no political overtones cloaked in a pretty melody with a golden hook. The song leapt out of the new crop of material as the obvious choice for a single and, once again, the timing could not have been more perfect for the Red Rockers. Their label, 415 Records, had just signed a distribution deal with the Columbia Records, the biggest label in the world. Columbia was looking to cash in on their investment and jumped on “China.” They put up the money for a video and put the full force of their promotion machine behind the single’s release. It all paid off in a big way. Although the record only reached #53 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, that was no longer the sole indicator of a “smash hit.” The record took off like a shot at college radio and reached #19 on Billboard’s recently instated Top Rock Tracks chart. Most importantly, the video went all the way to #2 on MTV which was then only two years old, but quickly becoming recognized as the new way to sell records. The album, Good As Gold, lived up to its name reaching a respectable #71 on the Billboard 200 album chart. The band spent 1984 on the road opening for superstar acts The Cars, The Go-Go’s, Men At Work and The Kinks.

ACUTE SCHIZOPHRENIA DISEASE

Flushed with the successes of “China” and Good As Gold, Red Rockers began planning for their next album only to find themselves in a situation similar to that which led to the departure of original drummer Patrick Jones. The band’s mainstream success had caused a backlash in the punk community which left the band without its core supporters and no one felt the sting more than James Singletary. Columbia had paired the group with producer Rick Chertoff, fresh off his multi-platinum success with Cyndi Lauper’s debut solo album, She’s So Unusual, who was looking to take the band to new commercial heights. James decided it was time to move on. He was replaced by Shawn Paddock out of Texas, a hot guitarist of the first order, but as far as the band dynamic was concerned, nothing more than a hired hand. Released in 1984, Schizophrenic Circus did not repeat the success of Good As Gold although the band’s reputation still managed to get them an opening slot on U2’s Unforgettable Fire tour.

In late 1985, Red Rockers relocated to Boston, Massachusetts. Boston had always welcomed the band with open arms and it seemed like a good place to regroup, but their efforts to find a new direction did not bear fruit. They disbanded late that year with John Griffith and Shawn Paddock lighting out for Shawn’s hometown in Texas. The band had rented loft space which gave them an affordable place in which to both live and work and Darren and Jim decided take over the loft while they began the search for musicians to form a new band. They didn’t have to look very far. They had begun to frequent an Irish pub in the neighborhood and one evening, they ran into a character named Johnny Cunningham.

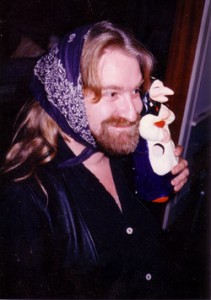

A SILLY WIZARD FROM ANOTHER WORLD

Johnny was born in Portobello, Scotland, a suburb of Edinburgh, in 1957 and began to play the violin at age six. He studied both classical music and traditional Scottish folk fiddling. By the tender age of twelve, he had already performed as a soloist with the Scottish Youth Symphony and was also recognized as one of the finest Scottish traditional fiddlers to come along in decades. At age 13 in 1970, he became a founding member of the acclaimed trio Silly Wizard in partnership with seasoned musicians nearly twice his age. Silly Wizard spearheaded the Scottish contingent of the Celtic music revival in the 1970s and gradually expanded into a five-piece unit which eventually included his younger brother, accordionist Phil Cunningham. Never one to rest on his laurels, Johnny left Silly Wizard in 1980 and moved to the U.S. seeking new musical adventures. He found continued success recording and performing as a solo artist and in a duo with his brother in the early ‘80s. In 1985, he and Phil formed a hybrid Scottish/Irish group, Relativity, with the brother-sister team of Micheal O’ and Triona Ni Dhomhnaill of The Bothy Band whose success rivaled that of Silly Wizard.

In 1986, when Darren and Jim ran into Johnny at the pub and they all hit it off (with Johnny’s wry sense of humor as much of a contributing factor as their common interest in music), it just so happened that Johnny was contemplating yet another adventure. He was looking to step out of the confines of traditional music and try his hand at Rock ’n’ Roll.

As the three musicians began planning to put together a band, the elephant in the room was the need for a special kind of singer-songwriter who could bring a fresh and original style to the table. As they haunted the clubs and sought advice from their friends, one name kept creeping up: Mark Cutler.

THE GRAND SCHEME OF THINGS

Mark had been lead singer, lead guitarist and songwriter for the Rhode Island band The Schemers for the better part of a decade. The band had enjoyed phenomenal success in the Northeast, winning the both the WBRU Rock Hunt in Providence and WBCN Rumble in Boston. They had won over a massive and devoted fan base and were arguably the most popular original band in New England. They had showcased at The Bottom Line and CBGB in New York City and had acquired a national reputation as one of the best unsigned bands in the country. Mark was considered one of the finest new songwriters on the horizon. They were the act just about everyone thought was most likely to succeed. But nothing happened. The major labels had all taken a look, but, for some inexplicable reason, they were never signed. It was a story eerily reminiscent of that of Beaver Brown, Rhode Island’s previous biggest original band who, by a stroke of luck, were offered the score to the motion picture Eddie And The Cruisers just as they were getting ready to hang up their Rock ’n’ Roll shoes after a decade in the trenches. But for The Schemers, there was no last minute reprieve, no happy ending. By the summer of 1986, Mark had come to the sad conclusion that The Schemers had run their course and it was announced that they would disband in early 1987 after playing out their previously booked schedule.

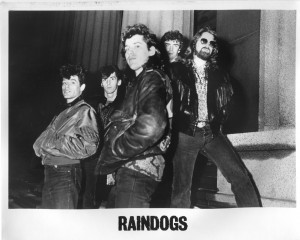

Darren, Jim and Johnny had continued polling their friends and contacts for a singer-songwriter for their band when they ran into Jim Sullivan. Jim was a Rhode Islander, a former musician who was then working for a tour merchandising company and had become friendly with the Red Rockers in his travels. He had known The Schemers since the beginning and strongly suggested that they check out Mark Cutler. They also ran into Jim’s cousin, John Cafferty, the leader of the Beaver Brown Band, who told them the same thing. The trio managed to catch one of Mark’s final performances with The Schemers and were collectively knocked out. They knew they’d found the right person for the job and arranged a meeting. Mark was intrigued and after taking some well-deserved and much-needed time off to chill out a bit and think things over, he decided to move to Boston and throw in his lot with Darren, Jim and Johnny in the Spring of 1987. They called the band Raindogs.

As the group began searching for its “sound,” it was decided the lineup would need one more piece, a second guitarist, and they brought in Ty Avolio. Ty had started off in the early 1980s as the drummer for Kilslug, a much heralded “dirge punk” band with several indie singles to their credit. He had dropped off the scene in the mid-1980s and had returned as a guitarist. The group set about working up arrangements of Mark’s mostly new material and soon zeroed in on the two songs which would become their first record.

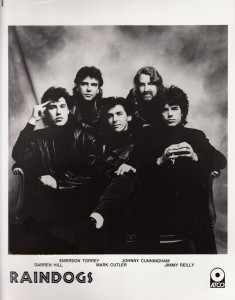

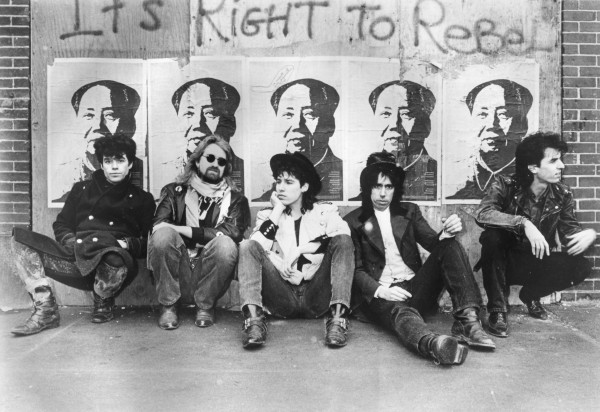

The original Raindogs (left to right): Jim Reilly, Johnny Cunningham, Darren Hill, Ty Avolio & Mark Cutler

“Lonesome Pain” b/w “Grey House” was released as a 12” single by the Boston-based Monolyth Records in the summer of 1987. The record is something of a tour-de-force especially considering that the band was in its infancy. The A-side is a pedal-to-the-metal rocker, driven by Cunningham’s percussive mandolin and droning fiddle, which sees the guitarists conjuring up the ghosts of Buffalo Springfield’s “Mr. Soul” and “Bluebird” and includes a musical quote from “Rock And Roll Woman” by a very Byrds-like 12 string electric. The B-side is just as strong, with a militaristic beat pounded out by the ex-Red Rockers rhythm section reminiscent of the pipe bands of Johnny’s Scottish heritage and the fife and drum corps of Mark’s New England roots, but with electric guitars instead of bagpipes and flutes floating over the top. But despite the glimmers of the touchstones of each of the band members’ influences and experiences, the collective sound was new and exciting and original. It was not The Schemers nor Red Rockers, nor for that matter, Silly Wizard nor Relativity. The record introduced the world to the sound of Raindogs.

THE ROOTS OF AMERICANA

Surveying the vast landscape of American popular music – trying to get a good look at “the big picture” – is as monumental a task in the early 21st century era of instant mass communication as it has ever been since the invention of the phonograph and the dawn of the radio age. There’s more happening than ever and there are more kinds of music than ever.

And nowadays, no matter where you look – Rock ’n’ Roll (Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers), Country (Steve Earle), Blues (Keb’ Mo’), and even Hip-Hop (The Roots) – the term “Americana” will inevitably creep up. But just what is “Americana” music?

In the aftermath of the British Invasion of the mid-1960s with the Beatles, the Stones and the Animals leading the way, young American musicians began following in their footsteps. Those with vision quickly realized that the Europeans were, for the most part, actually recycling various American roots music traditions back to the U.S. in the guise of a new kind of Rock ’n’ Roll. The young Americans, in turn, began incorporating elements of the traditions on which they’d been raised into their homegrown original music and thus, in the mid-late 1960s, was born the era of hyphenated musical forms: there was Folk-Rock (The Byrds, The Mamas & The Papas), Country-Rock (Poco, The Flying Burrito Brothers), Blues-Rock (The Blues Project, The Electric Flag whose motto, by the way, was “An American Music Band”), Jazz-Rock (Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chicago), etc.

Sometimes, there were so many ingredients in the pot that the music defied description as with Buffalo Springfield (surf, soul, folk, latin, country, R&B, bluegrass) and The Doors (jazz, R&B, Flamenco, classical, Beat poetry). Writers and critics struggled to find a name for the new music. For lack of a better term, it was all heaped together under the umbrella term “Rock.”

These hybrid forms of popular music continued to develop and evolve throughout the 1970s and ‘80s and there continued to be no term to describe them when Raindogs came together in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1987.

Shortly after Raindogs came into existence, the music press finally hit on an all-encompassing term which fit the bill, “Americana.” It seems, however, that Americana is not so much a musical genre as a catch-all description for musical styles which often defy description. It’s an umbrella term which came into usage in the late 1980s and early ‘90s to bundle together various musical styles which shared one common trait: a devotion to the traditions and principles of one or more styles of American or western European roots music.

By wearing their far-flung influences (cajun, Zydeco, punk, new wave, blues, Scottish and Irish traditional, Hank Williams, Dylan, the Stones) on their collective sleeve, Raindogs positioned themselves at the forefront of the Americana movement and were pioneers into this new territory which, twenty-five years on, has become a full-fledged tradition of its own with a Grammy category and its own sales and airplay charting systems.

Now that Willie Nelson is too “country” for Country, Alison Krauss too “pop” for Bluegrass and Neil Young too “all over the map” for Rock ’n’ Roll, they are now classified as Americana artists. As charter members of that club, I’d say, for the Raindogs, that’s pretty good company.

BROTHERS IN ARMS

By the time of the record’s release, the band had already made their live debut. There had been a lot of anticipation surrounding the new group and Raindogs did not dissapoint. One of their earliest reviews stated that, “Cutler drives a locomotive and Raindogs left blood on the tracks.” Things were looking up, but before year’s end, musical differences had arisen between Avolio and the rest of the group. Although a fine guitarist, Ty was on his own musical path and his vision did not always mesh with the overall direction of the collective sound. For Mark, the missing ingredient which could take Raindogs to the top was Emerson Torrey, his right-hand man from The Schemers.

During The Schemers run, Mark and Emerson had developed a style of guitar interplay and close harmony singing which had become the cornerstone of their sound. The addition of Emerson to Raindogs would create a truly cohesive unit. Mark headed down to Providence to visit his old friend.

Since the demise of The Schemers, Emerson had been working with Tom Keegan & The Language. Keegan was another of Rhode Island’s great unheralded songwriters, formerly the lead singer of The Hometown Rockers, the new name of the aforementioned Wild Turkey band when they made the switch to playing original music. The Language was doing pretty well, but Tom and Emerson would go out as an acoustic duo on off nights to supplement their income. The pair was at The Backstreet Bar & Grill in Providence one night in late 1987 when Mark Cutler came in. Mark told Emerson about the departure of Ty Avolio and asked if he would consider joining Raindogs. According to Emerson, he told Mark that he’d need some time to think about it and Mark said that would be fine. It did not take long. Just one minute later, he turned to Mark and said, “I’m in.” The Cutler-Torrey team was back in action.

In no time at all, Emerson was absorbed into the lineup and the band hit the streets. Their reputation as a killer live act grew quickly as they made the rounds of southern New England’s showcase clubs: The Rat, The Channel and The Paradise in Boston; The Living Room, Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel and The Last Call Saloon, the Schemers’ old haunts in Providence; and Toad’s Place in New Haven, Connecticut. By the end of 1987, the band had taken on management.

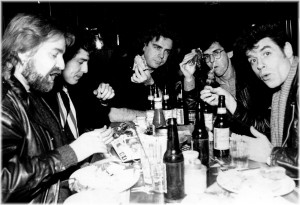

Raindogs in repose: The band enjoying a rare moment of downtime at the legendary downtown Providence bar and grill, Leo’s.

On October 19 of that year, R.E.M. and 10,000 Maniacs were in Rhode Island for a concert appearance at the Providence Performing Arts Center (formerly the Palace Concert Theatre). Also in town that evening was Bill Flanagan. The former NewPaper writer had moved on to Musician magazine and was working on a story about R.E.M. After the show, Bill suggested to Peter Buck that they head over to Lupo’s to catch a new band, Raindogs, which featured two of his old pals from The Schemers. Buck was knocked out. He sat in with the band, proposed producing an album for them and wound up in a long musical discussion with Johnny Cunningham. Also in attendance at Lupo’s that evening was Richard “Paco” Zimmer.

Peter Buck of R.E.M. joins Raindogs on stage at Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel in Providence, October 19, 1987

In the early 1980s, Paco had operated Center Stage, a showcase club in East Providence and was well-known as a champion of Rhode Island music. By 1987, he had achieved great success as a tour accountant and tour manager for national acts (Boston, The Allman Brothers Band, The Stray Cats, ZZ Top) and was a partner in an artist management firm. He, too, was knocked out by the former Schemers’ new band and by year’s end, had signed on as Raindogs manager. For the next year or so, Raindogs continued honing their sound, polishing their act and expanding their repertoire of Mark Cutler originals. Paco made the rounds of the record companies and arranged showcases in New York City at Irving Plaza, The Ritz, The Beacon Theater and The China Club. In the summer of 1989, Raindogs signed with Atco Records.

Atco Records was a subsidiary of Atlantic Records (which itself was a division of WEA, the gigantic Warner-Elektra-Atlantic entertainment conglomerate). It had been the home of Cream, Buffalo Springfield and dozens of other artists whose work had influenced the members of Raindogs and seemed like a perfect fit. They were paired with producer Neil Dorfsman whose previous credits included albums with Paul McCartney, Bruce Hornsby & The Range, Randy Newman and the multi-platinum Brothers In Arms by Dire Straits. On the surface, this seemed like another perfect fit, but before long, the first fly appeared in the ointment.

Problems arose almost immediately after Neil and the Raindogs entered a New York City studio to begin work on the album. Despite the tightness and power the band had achieved as a live act, Dorfsman was not getting the sound he wanted out of them in the studio. He suggested to Mark that if they brought in some studio musicians to work on the project, he could virtually guarantee them a hit. Suddenly, on the eve of finally reaching his life’s goal – to record an album for a major label – Mark was faced with several artistic, ethical and moral dilemmas. On one hand, it had been a long, hard road to get where he’d finally arrived and a hit record would start him on the road to stardom and everyone would benefit. On the other hand, the record would not represent the sound and “intent” of the Raindogs and he would be asking the musicians whose collaboration and support he’d come to cherish, including that of one of his best friends and longest-running musical partner, to become his backing band.

To put this into perspective, Dorfsman had used an identical approach when he worked with Dire Straits. As anyone who’s heard the band’s 1983 live album Alchemy or seen its companion concert video version can attest, Dire Straits had become one of the best live acts on the planet. Just two years later, with the same musicians in place, Neil had convinced Mark Knopfler to use studio players to record the majority of the ironically titled Brothers In Arms. In the studio, he replaced virtually the entire band – bar Knopfler – with top session men including bringing in Omar Hakim to sub for Dire Straits’ incredible and legendary Scottish drummer, Terry Williams, and using bassists Tony Levin and Neil Jason in place of John Illsley, the only other original member of the band who was also one of Knopfler’s oldest friends and his musical and business partner of more than a decade. Sound familiar? But, one cannot argue with the results: Brothers In Arms is one of the greatest Rock ’n’ Roll albums of all time and one of the best-selling albums in history, nine times Platinum – that’s 9,000,000 copies – in the U.S. alone.

Mark stuggled with the problem for a brief time, but found his answer in advice which came from an unlikely source, New York session drummer Anton Fier, one of the musicians on call to sub for the Raindogs. Speaking with Mike Boehm in an interview in the Los Angeles Times (March 22, 1990), Mark explained it this way. “(Fier) said, ’Mark, it’s up to you whether you want to be famous and feel terrible for a few years, or stick up for your band.'” Mark stuck up for the band. He told the Raindogs to be prepared to get dropped because he was going to call Atco to tell them they wanted a new producer. Cutler found a sympathetic ear when he called Atco president Derek Shulman. Derek was himself a musician and had spent two decades on the front lines of the Rock ’n’ Roll wars as a member of England’s Simon Dupree & The Big Sound in the 1960s, then as one of the principals of the prog-rock band Gentle Giant until 1980. Derek suggested the band meet with Peter Henderson.

Peter had a reputation for turning bands which were not easily classifiable into superstars. He had guided Supertramp from a marginally successful art rock band into a quadruple platinum act with Breakfast In America and Derek knew him from his previous job running Mercury/PolyGram when he had helped move Rush beyond “cult” status with the million-selling Grace Under Pressure. Peter Henderson liked what he heard and Raindogs liked Peter Henderson. The new team hightailed it out of New York City and holed up at The Outpost, a studio in the Boston suburb of Stoughton, Massachusetts.

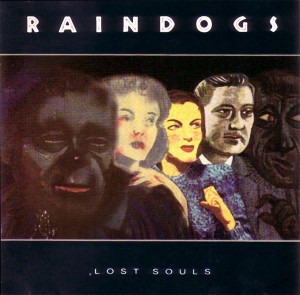

LOST AND FOUND

Back on their home turf in southern New England, Peter and the Raindogs wasted no time. As a musician himself, Henderson recognized the importance of artistic control and agreed to co-produce with the band. The Raindogs set up as they would on stage and the basic tracks were cut live in the studio to capture the raw power of the band. Once the lead vocals and solos were in place, there was little need for “sweetening” and overdubs were kept to a minimum. As for “studio musicians,” the band simply called in friends and acquaintances from the local talent pool to add the final touches: a horn section led by saxophonist Gordon “Sax Gordon” Beadle, Jim Fitting of Treat Her Right on harmonica, ex-Schemer Dick Reed on keyboards and accordion, and Peter Henderson himself on keyboards. Raindogs stayed true to their roots even when it came to the artwork. Mark Cutler paid a visit to Rhode Island-based artist Dan Gosch and came across an untitled painting in his studio which he immediately knew would convey the message of the band and his songs – lost souls.

The resulting album was a triumph. For Mark and Emerson, it was an affirmation of their dedication and belief in Mark’s talents which had sent them on this journey more than a decade before. For Johnny, it was confirmation that his instincts had been correct when he’d felt it was time to step outside the confines of traditional folk music. For Darren and Jim, it was a second chance at stardom after their previous successes with Red Rockers and Stiff Little Fingers had proven unsustainable. And they didn’t have to sell out to get there!

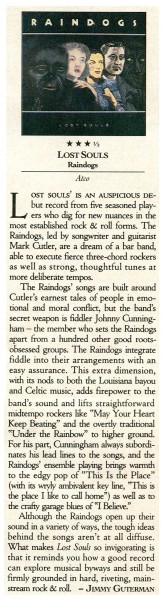

Released in January, 1990, Lost Souls was well received across-the-board including a three-and-a-half star review in Rolling Stone by Jimmy Guterman which stated, “…it reminds you how a good record can explore musical byways and still be firmly grounded in hard, riveting, mainstream rock & roll.”

The single alone was well-worth the price of admission. “May Your Heart Keep Beating” takes the listener to a place where The Who might have wound up if they hadn’t imploded after The Who By Numbers while still maintaining the clear and unique identity of Raindogs performing a Mark Cutler song. The track performed well at both college and AOR and the label put the full forces of its publicity machine behind the band and the album. Over the course of the year, Raindogs undertook national tours with Warren Zevon and Don Henley and the reviews were quite often more favorable to the opening act than to the headliners. When the dust cleared, it was apparent that Mark Cutler and the Raindogs were on the verge of stardom and, after a short breather for Mark to put together new material, the band regrouped when the bell rang for round two.

THE REPO MAN

Excitement was running high on the Providence-Boston axis of the southern New England music scene when it was announced that Don Gehman would be the producer of the second Raindogs album. Gehman had a reputation for providing the same kind of magic touch as Peter Henderson when it came to moving acts up to the next level, but his client base had much more in common with Raindogs than Supertramp or Rush.

Don had signed on as John Mellencamp’s co-producer for 1982’s American Fool, his last album as “John Cougar.” The pair mined platinum by steering away from the hard rock overtones of his previous work and into the more blue collar neighborhood where Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen were living it up. Their partnership continued for three more multi-platinum LPs (Uh-huh, Scarecrow and The Lonesome Jubilee) and a slew of hit singles which saw Mellencamp revert to his true last name, exit the music business fast lane by setting up his own studios in his home state of Indiana, tackle social issues and otherwise raise the bar on his lyric writing, and introduce acoustic folk and country instruments into his band placing him in the same early Americana territory as Raindogs would explore on Lost Souls. Between Scarecrow and Jubilee, Don had taken the same approach with college radio favorites R.E.M. by bringing them out to Mellencamp’s studio in the midwest where he helped slide them into the mainstream with Life’s Rich Pageant which earned them a Gold album and included their first Hot 100 single, “Fall On Me.” To top it all off, when Don signed on to produce the Raindogs, he was fresh off co-producing Bruce Hornsby’s third album, A Night On The Town, another successful act operating with the same musical and artistic sensibilities as Mark and the band.

It seemed like a match made in heaven: with Don Gehman in the producer’s chair, the new batch of Mark Cutler songs should translate into Platinum. But, something was lost in the translation.

The Raindogs were ready to expand their palette both musically and technologically. They were excited by the sounds of rap and hip-hop which had entered the mainstream over the course of the 1980s and wanted to incorporate some of those sounds and techniques into their music. They were also eager to explore the possibilities presented by the new digital recording technologies which had become available – to utilize the studio as an “instrument” as opposed to a facility. Don Gehman, keeper of the “heartland rock” flame that he was at the time, did not object. In fact, he was also eager to explore some new territories beyond the borders of a guitar-driven rock combo and enthusiastic about the possibilities which producing Raindogs presented. The team enlisted the aid of Phil Shenale, a well-regarded studio keyboard player who was busily making a name for himself by adding synthesizers, loops, samples, drum machines and other modern touches to recordings by mainstream acts who were trying to keep up with the times. Phil’s motto was “On the cutting edge of old technology” and he’d previously worked with a wide range of artists including Frankie Valli, The Beach Boys, Robert Cray, Rick Springfield and Billy Idol.

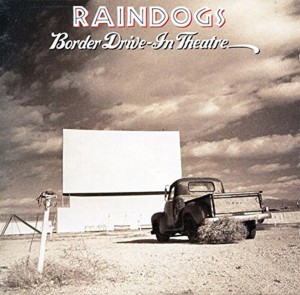

Released in 1991, the resulting album, Border Drive-In Theatre, was not well received. Perhaps the biggest missteps on the production end were the use of drum machines and the underutilization of the fiddle and mandolin. The rhythm tracks were arranged by Jim Reilly and Phil Shenale and reflect Jim’s general style, but the swing and power of his post-punk playing was missing. Johnny Cunningham’s contributions were minimal and used for sweetening instead of as instrumental hooks and he did not solo on the album. (He did, however, co-write with Mark and Phil one of the album’s best songs – the exceedingly lovely “I’ll Take Care Of You” for which he created a “Yesterday”-styled string section with violin overdubs and Phil’s synths.)

There’s plenty of Cutler-Torrey guitar interplay and harmony singing and the bass seems to be Darren’s bass guitar for the most part, but what’s missing is the power of the Raindogs playing live which they’d come so close to capturing on Lost Souls and might have nailed this time with Don in their camp.

On the plus side, the keyboards, mainly synths, are a welcome addition to the arrangements and the various loops and samples do their jobs and give the album a modern glow. The album’s “raps” are delivered by two unlikely MCs and both work marvelously well. Cult film actor and Hollywood character Harry Dean Stanton has the speaking part on “Some Fun,” a Cutler/Shenale reworking of The Schemers best-known, best-loved song “I Want Some Fun.” Iggy Pop, punk godfather and former lead singer of The Stooges, adds some truly spooky touches (and cuss words which somehow managed to escape the notice of the RIAA’s Parental Advisory board) onto “Dance Of The Freaks,” Mark’s darkest song to date.

In hindsight, Border Drive-In Theatre was a noble experiment and is a fine album overall. It’s a “must-have” album as it contains some of Mark’s all-time best songs (“Look Out Your Window” being a case in point) and finest recorded vocals up to that time. Maybe they just went a little too far for their fan base. Maybe it was just a little bit ahead of its time. (The Rolling Stones would wind up squarely in this same territory with Bridges To Babylon, but not until 1997.) Or maybe that’s all just conjecture.

Probably the single biggest factor in the album’s quick trip to the cut-out bins was that Atco Records was undergoing a restructuring and Raindogs got lost in the shuffle. Another Atlantic subidiary, EastWest Records, their contemporary R&B division, was being folded into the label and word had come down from WEA’s corporate headquarters that the new focus would be on the Top 40 and urban end of things and that the Rock ’n’ Roll was to be fazed out. It was announced that Sylvia Rhone, the head of EastWest, would be taking over the day-to-day operation and that Raindogs champion Atco president Derek Shulman would be moving into a higher position at corporate once the merger was complete. (Atco/EastWest operated until 1994 when Atlantic retired the Atco name altogether and changed the logo to simply “eastwest.”)

The first single, “Some Fun,” took off in the northeast where most of the band’s fans were familiar with the original Schemers version, but it failed to catch on nationally. A second single, a cover of bluesman Wilbert Harrison’s “Let’s Work Together,” was rush-released (just a couple of weeks and two catalog numbers later), but it, too, did not catch on. Perhaps this was due to the fact that the song had already been a hit four times in the previous twenty-five years. In 1962, Harrison had scored a major R&B hit with the song’s original incarnation, “Let’s Stick Together.” He re-cut it in 1969 as “Let’s Work Together” and it reached #32 on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1970. His pals Canned Heat then followed his version with a cover which went to #26 in the summer of the same year. And then Roxy Music singer Bryan Ferry had a worldwide smash (except for the U.S. where it was an FM favorite) in 1977 with his take on the original lyric, “Let’s Stick Together.” Raindogs version is terrific and a fine album track, but does not bring anything “new” to the song and it was probably just too soon to think that another version could make a run up the charts.

Despite the upheavals at the label, the company tried again and released a third single, “Baby Doll,” but when that failed to attract any attention at radio, they let the album die on the vine.

NOBODY’S GETTING OUT

When Border Drive-In Theatre was released, expectations in the Raindogs camp were high and the band headed out on tour with Bob Dylan. Things began to unravel quickly, however, when the label gave up its promotional campaign for the album and withdrew its tour support when none of the singles charted. Bookings began to fall off which caused tensions with their management and Raindogs split with Paco Zimmer. Their Atco contract was not renewed.

They returned to Boston where their original, loyal fan base had propelled “Some Fun” to the top of the Boston radio charts for six weeks and went back into the clubs while they planned their next move. But lack of a record deal soon forced Johnny to retreat to traditional music where his artistry was still in great demand and the band decided to call it a day. They parted as fast friends.

Darren became the bass player for Paul Westerberg’s first post-Replacements band. Jim Reilly returned to Belfast. Emerson and Mark moved back to Rhode Island and more or less dropped off the scene for a few years. It would not be long, however, before they returned to music. Emerson opened a recording studio and, in 1995, Mark launched a solo career which would become his crowning achievement.

Up In The Air

MARK CUTLER: THE SOLO YEARS

by Scott Duhamel

THE BIG PICTURE

As much as Mark Cutler’s reputation as one of the all-time great unsung heroes of Rhode Island rock rests on his legacy as the leader of The Schemers and Raindogs, as a high shaman of live performances that have taken place everywhere in New England from backyard beer parties to sweaty punk clubs to civic centers and performing arts theaters, and as a massively adept and sometimes toe-curling guitarist, his place of respect has always been anchored around his masterful, incisive, and astoundingly prolific grasp of the fine art of songwriting.

Cutler has proved, time and time again, through his ever ongoing permutation of styles, bands, and sounds, that his music, at its essence, is about the craft of the song. Whether he is delivering a song in classic 4/4 style, old school electric blues, exuberant garage, crash-and-burn punkarama, white-boy soul, twangy Americana, or a plaintive acoustic whisper, both his rabid followers and first-time listeners can’t help but shake their heads in affirmation at the song within the style. In many ways, despite the ever-hovering local legend status of both The Schemers and Raindogs, his solo career presents the clearest evidence of Cutler the exemplary songsmith.

Throughout his career, whether he was in the midst of putting his songs online or receiving radio airplay (remember those long, gone days?), recording for major labels or doing it DIY, playing the local joint or standing tall in the spotlight of a big venue, it’s always amazed me how much of his audience know the songs, verse-to-chorus, guitar break-to-drum beat. During the absolutely countless times I’ve seen him perform there always is a point that makes me break out in a sly smile: when I glance around at my fellow listeners and watch so many of them stomp their feet and sing along with Marky. Somehow, without the traditional and acknowledged measurements of pop music success (fame, fortune, sales, continued song play), Cutler has achieved something remarkable. In his bailiwick, his hometown and its adjoining region, he’s made his lifetime of material a known quantity. Even with a constantly changing songbook audiences recognize, remember, and revel in a good portion of whatever set he is delivering that night, in whatever style. Yes, throughout the country in the ever shifting musical scenes and creative hotspots there are those musicians who live in the same pop cultural landscape as Mark Cutler; local heroes, incendiary scene-makers, leaders of the local pack who somehow crack the bigtime for their 15 seconds only to get sent back to the perceived minor leagues again, yet many of them persevere, continue to follow their muse and make music for themselves and for a non-national audience, yet they never lessen their commitment, inventiveness, or more importantly their spirit. In Rhode Island, that oh-so- familiar tale probably belongs to Mark Cutler above all else, and for that we should consider ourselves damn lucky.

I often wrestled with the idea that Rhode Island’s continued celebration of Cutler’s music and his progression of musical efforts results from the typical tenets of provincialism—He’s Ours, Not Yours—and the simple fact that the arc of his professional endeavors is delineated by three acts that pop mavens truly dig. Act 1 is the bootstraps and local roots part, all sweat, balls and raw talent, and the defeat of the odds. Act 2 is the flirt with the big leagues, increased press and notoriety, adoring notices and swelling crowds, vested interest by the outside world, and most importantly, The Industry, and finally the big label signing and the subsequent bigtime touring. Act 3 is what seals the deal. The dissolution of the band, the dropping by the label, the formation of a new group or groups, new recordings and songs, and finally, back into the soft, glowing embrace of the place where it all started – home, sweet, home. He’s Ours, Not Yours, the wounded warrior back where those that know him and love him, and most of all, truly appreciate his special talents, can salve his wounds, massage his crushed ego, and wistfully pat each on the back, all the while tawking the tawk about what coulda, shoulda, woulda.

Of course this diminishes said artist by raising the questions of whether he was as unique and special as the local mopes and dopes thought he or she was. Was it regional pride, often dictated by aggressive advocacy, self-involvement, and less-than-stellar artistic judgement that led to the rise and begat the fall? Was, and is, Mark Cutler that dynamic a performer, band leader, guitar slinger, rock and roller, or tunesmith who can actually compare with the big leaguers, cult artists, and influences that have been cited when nitcrits and real peeps have discussed his output? We are talking a wide range of comparative musical kin: Elvis Costello, Tom Petty, Johnathan Richman, Lou Reed, Jeff Tweedy, Willie DeVille, Alejandro Escevedo, Tom Verlaine, among others; never mind all the usual baby boomer suspects: Dean Martin, John Coltrane, Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, Neil Young, Brian Wilson, The Beatles, The Kinks, The Who, The Rascals and, most especially in Cutler’s case, Frank Sinatra, The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. His ascendency into the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame signals yes. Yes, indeed, and his recorded oeuvre proves it.

Over the years, in between the shouted choruses, and sing-along stanzas, Cutler has continually written insightful, thoughtful, dare I even say, often poetic lyrics, often smack dab in the midst of the traditional, two guitar, bass, drums and vocalist style he most often works in. His songs are peopled with blue collar and regular Joe types, many with tentative aspirations, a whole lot more with dashed dreams and deep down resignations. Social forces bleed in, more often in the background, setting the stage for the protagonist’s propulsion, and even more often, resulting in heroic or heart-breaking failure. Cutler’s subjects are wounded (by love, by excess, by their own actions), and many of them are more aptly seeking some sort of unexplainable state of grace, a theme that may indeed be enforced by the songwriter’s early growing-up-R.I.-Catholic roots.

The Cutler songbook is chock full of characters seeking “Soul Salvation,” wanting “Some Fun” that is more spiritual than earth driven, exploring “Sweet Pain,” debarking on a “Salvation Cruise,” beginning to “Fall Apart,” getting “Lost in the Flood,” veering into “Lonesome Pain,” getting scorched by a “Soul Flame,” roiling in their own “Ton of Regrets,” basking in the full troughs of romantic “Misery,” all in all constantly searching for a “Better Way.” Yet, being characters with the obvious desires, both base and simple, they go “Walking in the Night,” diving deep into the “Valley of Love,” find themselves “Drinking in the Afternoon,” stuck in “Another Hall of Mirrors,” striving to have a “Real Good Time,” or playing imaginary games with “Future Skeletons” or “Doc Pomus’ Ghost.” Of course there is occasional, maybe temporary transcendence, of the mortal kind, by momentarily being transported or transfixed by “Lon Chaney’s Moon,” finding solace “Under the Rainbow,” by finding “Dreamland,” by actually “Hovering,” by being “Up in the Air.”